October 7, 2024

“It Smells like Cock Here”: Warmongering, Masculinity, and Repeating History

The title probably sounds entirely ridiculous and out of place, yet there is a connection with the subtitle. Indeed, when it comes to warmongering and masculinity, historical examples abound.

Inspiration behind this post came after I read the excellent nonfiction book The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, by Christopher Clark. Among the many intriguing details, a chapter aptly titled “A Crisis of Masculinity?” proved eye-opening.

So let’s dive deeper into the connection between warmongering and masculinity (here clearly meant as toxic), and see how dangerous it can become to ignore the lessons of history. But first, let’s begin with a hilarious anecdote – which gave the title its name…

Mothers in Bars Full of Men…

So here’s the explanation behind the “smells like cock” title, based on a true story that occurred a long time ago.

A group of young male students visit a bar, together with the mother of one of them, who’s come to visit the city. Not awkward at all, right? If the picture of half a dozen 20-year-old guys entering a bar together with an extrovert, rambunctious 40-something-year-old woman (who happens to be the mother of one of them) sounds cringe to you, you’d be absolutely right. American Pie vibes and all that…

And yet it gets worse: Upon entering the bar, the group realize there are only men there. No women; zip; nada. And then suddenly – for creative effect, we can imagine a brief silence between songs – the mother utters: “Hmm, it smells like cock here…”

It’s a funny incident to remember, but it has created… sociohistorical associations for me.

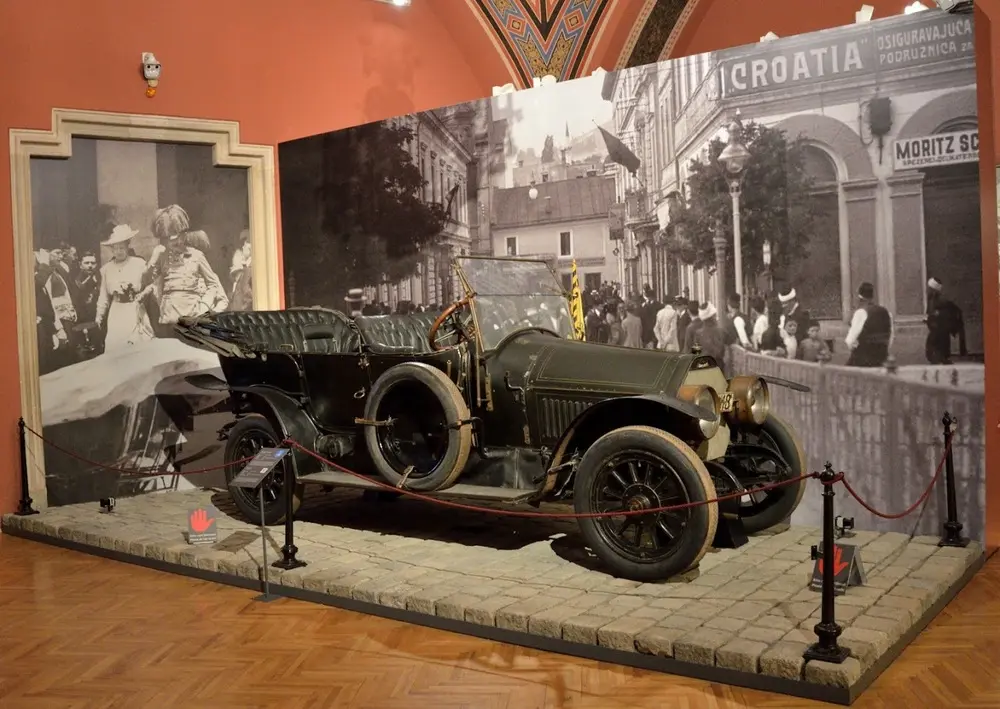

Warmongering Masculinity: the Ukraine Shift

When Russia attacked Ukraine in early 2022, it was a huge shock to many people. To others, it wasn’t – and indeed, in retrospect, even those who were shocked realized it was all plain obvious to expect. Vibes of the Great War and all that.

Virtually overnight, the world had changed in radical ways. Finland and Sweden scrambled to get into NATO, abandoning their decades’ old neutrality. Eastern European countries (soon followed by others) began increasing their military readiness, spending more and more on defense.

There was a cultural shift, too. YouTube suddenly became inundated with – cough, cough – geostrategic analysts who “reacted” to military videos praising this or that army.

Hell, many of those videos were official productions at a state level: Countries’ armed forces channels create – with impactful effects and music – heaps of videos showcasing the military might they possess.

To me, the world suddenly began “smelling like cock”…

Warmongering Masculinity in The Great War

In Clark’s book and particularly in the chapter “A Crisis of Masculinity?” we find some remarkable details regarding the psychological motivations of the Great War’s protagonists. Some of them are worth quoting verbatim, as they are highly revealing:

Historians of gender have suggested that around the last decades of the nineteenth and the first of the twentieth century, a relatively expansive form of patriarchal identity centred on the satisfaction of appetites (food, sex, commodities) made way for something slimmer, harder and more abstinent. At the same time, competition from subordinate and marginalized masculinities – proletarian and non-white, for example – accentuated the expression of ‘true masculinity’ within the elites. Among specifically military leadership groups, stamina, toughness, duty and unstinting service gradually displaced an older emphasis on elevated social origin, now perceived as effeminate.

Even more revealingly:

Yet these increasingly hypertrophic forms of masculinity existed in tension with ideals of obedience, courtesy, cultural refinement and charity that were still viewed as markers of the ‘gentleman’. Perhaps we can ascribe the signs of role strain and exhaustion we observe in many of the key decision-makers – mood swings, obsessiveness, ‘nerve strain’, vacillation, psychosomatic illness and escapism, to name just a few – to an accentuation of gender roles that had begun to impose intolerable burdens on some men.

All this led to fatal consequences:

The nervousness that many saw as the signature of this era manifested itself in these powerful men not just in anxiety, but also in an obsessive desire to triumph over the ‘weakness’ of one’s own will, to be a ‘person of courage’, as Walther Rathenau put it in 1904, rather than a ‘person of fear’. However one situates the characters in this story within the broader contours of gender history, it seems clear that a code of behaviour founded in a preference for unyielding forcefulness over the suppleness, tactical flexibility and wiliness exemplified by an earlier generation of statesmen (Bismarck, Cavour, Salisbury) was likely to accentuate the potential for conflict.

These excerpts are remarkable. But have we learned the lessons?

The Forgotten Lessons of History

A recent study here in Finland showed that 1 in 4 Finns support sending troops to Ukraine to fight against Russia. This is interesting in itself – for reasons beyond the scope of the post – but the key element that should give us pause is this:

One in three men favoured sending troops, compared to one in six women. Younger people also showed greater support for deployment than older generations.

Not only are men twice as eager to send troops to war, but younger men more so than older men. In other words, the people more likely to be sent to a war zone are those more eager to go.

This might sound paradoxical at first, until we realize a couple of things: Firstly, younger generations have no real understanding of war; not even a vicarious one. Someone who is now 60 might or might have not fought in a war, but they definitely have friends or relatives who have – perhaps even with terrible consequences. On the other hand, younger generations don’t really have an affectively impactful experience of war; not outside playing a video game.

The second element worth exploring is an increasing lack of purpose bedeviling younger generations. In a world full of (anti-)social media, consumerist hells, binary dilemmas, and polarization, younger generations subconsciously look for crises in order to establish a point of moral reference. That is to say, they try to discover meaning in a framework radically different from their humdrum reality.

The Sociocultural Gender Gap

Warmongering masculinity is a result of an increasing sociocultural gender gap: Younger women are becoming more liberal, whereas men more conservative. This leads to an increasingly more insecure, less educated, more right-leaning (= warmongering) form of masculinity that can become tremendously dangerous.

The world smells like cock because insecure men (young and old) need death and destruction to verify themselves. This has happened again and again, and it will continue to happen. After all, as K.K. Ruthven argues in Critical Assumptions: “‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’, wrote Santayana, but it is equally true that those who can remember the past are condemned to watch it repeated by those who can not” (p. 113).

Or, in the words of the matchless George Carlin:

I don't show you ads, newsletter pop-ups, or buttons for disgusting social media; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?

(If you'd like to see what exactly you're supporting, read my creative manifesto).