October 31, 2022

Authors Talk: Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt

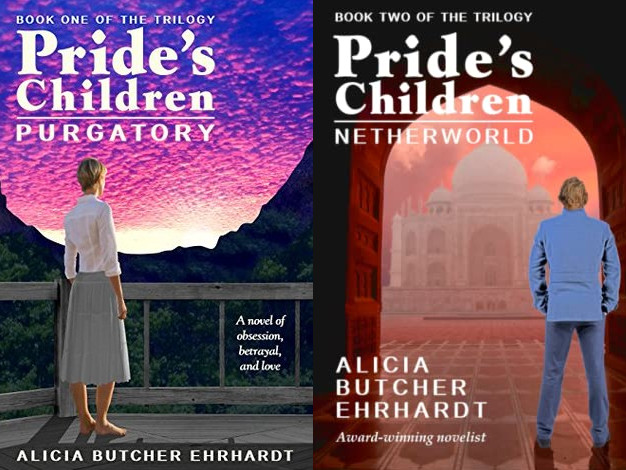

Another “Authors Talk” post. You can think of it as an author interview and, indeed, that is the name of the blog category. However, I prefer to see it as a friendly chat between fellow authors. Today I’m having this virtual discussion with Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt, author of the Pride’s Children Series. A list of useful links to Alicia’s work can be found at the end of this post.

A Talk with Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt: Pride’s Children

Chris: Your newest book, Pride’s Children: Netherworld, has been recently published. I understand it’s the second book of the trilogy – the first being Pride’s Children: Purgatory. Would you like to talk a bit about your work, particularly for the benefit of readers not familiar with it? How does it feel to read such a novel? What are the emotions and dynamics involved?

Alicia: The whole point of this trilogy is to make the reader feel. My intent – besides telling an entertaining, plausible, complex layered story that might be true – is to let the reader live and experience the story only from the deep close POV of the three main characters. Not first-person – I’ve seen that done and find it disruptive to identify with one character and then have to switch to another.

Margaret Atwood’s Life Before Man does that, and I wasn’t comfortable with the total identification that first person requires being ripped up every time she changed POV. Well done – but my reaction to it was that I never wanted to do it that way. Multiple third is, I think, easier on the reader – and just as close.

Characters and Dynamics

One of my main characters, Dr. Kary Ashe, is disabled, a recluse with severe limitations on her energy, and I wanted the reader to experience that first-hand. All the little daily and hourly tradeoffs – but only when they popped up a bit more than usual, and demanded her attention.

My other two main characters are Andrew O’Connell, an Irish actor on the cusp of major stardom when role choices, reputation, even appearance are critical – do we have a potential Robert Redford type or a Gene Hackman type? Plus the whole international side – and he comes to prominence by playing Roland in the eponymous movie based on the French epic poem (think that can’t be done?)

And Bianca Doyle, beautiful, sultry, Hollywood’s current princess and America’s Sweetheart – wondering if she can make the transition from ingenue to actress (yes, it’s 2005 and “actor” hasn’t completely banished “actress” for women) who will always have work – and she chooses to make this statement by directing a biopic of Lewis Carroll’s life and historically possible infatuation with his mentor’s governess. She has settled on Andrew, her costar in a movie set near Kary’s home in New Hampshire, as a candidate for personal and professional success. After she dumps the current live-in hunk – ex-action star Michael (who sadly isn’t performing up to his promise).

Andrew meets Kary on a New York late-night talk show – where she’s been persuaded to speak up for her illness – two people who paths under normal circumstances would never meander near each other.

To complicate matters, Kary, divorced, has no intention, ever, of saddling anyone with the defective wife which she is sure she would be – the world and her conscience would never consent. She is perfectly happy as a hermit, writing novels. Well-received, popular novels. At her own speed.

Purgatory set up the relationships, the friendships, the near misses – and then Incident at Bunker Hill is in the can and its cast scatters.

Netherworld asks what could happen to take all these relationships to a much higher level – because the world of film is a tight inbred microcosm. And does it in India, on the set of a Bollywood/Hollywood coproduction. And in the Czech Republic for the eponymous film Dodgson. And Ireland. And Hollywood.

Personal and professional lives meet, entwine, break. Things are not what they seem.

Plotting and Planning

Chris: Thinking about the magnitude of details contained in such works – and also as a result of our various intriguing discussions on the matter – I’m in awe of how much effort it goes into producing narratives of this scope that are still coherent and engaging. What are the greatest challenges in producing such a trilogy? I’d be particularly interested in hearing how an author resists the temptation to go back and change something written at a much earlier stage, based on new ideas.

Alicia: I’m an extreme plotter, because a lot of the plot points have time constraints, and I didn’t want plot holes. The characters kept developing as I asked questions, but the original idea – which the more I examine, the more I see had additional sources other than the obvious main threads – hasn’t changed: what would it take in the real world for this to happen?

Pieces accumulated: remember Paul McCartney’s ill-fated marriage to Heather Mills? The place in the American pantheon – celebrities, especially film stars, occupy – which in other nations might be filled by some version of limited monarchy. Medical research – and medical disbelief of “invisible illnesses”. The progress in the world of in vitro fertilization and reproductive technology. The very convoluted informational world of the unsupervised and unvetted “internet”. Music – and the vanity bands some stars love. Financing films – and how the “angels” feel entitled to “help.” It’s like the “everything” bagel.

I’m slightly bemused by the fact that the trilogy, when finished, will be as long as GWTW – I didn’t set out to do that, but love the scope and space it allows. And I am unreasonably pleased that in something that long, everything is connected. And have pared the rest to the absolute minimum: if something isn’t part of three or four threads, it didn’t make it. Maybe that’s the way the brain of a former computation physicist is wired?

A Talk with Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt: Writer’s Life

Chris: It’s often said writers hate writing and hate not writing; they only like having written. Do you feel the same? How has writing affected your everyday life, both positively and negatively?

Alicia: I find the period of “having written” leaves me bereft. The writing is so intense, the connecting so demanding, that it leaves a void when I don’t want to change another word. The list of what a scene must accomplish is long and detailed – but then it’s over, and I rarely have to go back to tweak some small detail. During the writing of a scene it seems as if it will never coalesce – and then suddenly it has. And the scene goes into its slot in the whole. Linearly, which still amazes me. Somewhere deep in my brain these connections were formed; I’m just mining them.

When I’m not writing – this past month since the publication of Netherworld I’ve had to deal with some major pandemic-postponed physical problems, and am still recovering from the meds’ effects on my brain – things aren’t “right”. My identity is writer, not author. When the right words and sentences survive the winnowing of all the versions and become canon, I’m always surprised. And pleased. As if it was there, somewhere, underneath, waiting to be brought to the surface.

I know my methods – developed because I cannot manage whole drafts at a time – are odd. I know the plotting – with the interconnectedness of Dramatica – would drive someone else mad. Even the certainty would boggle many minds. But I stand by the results – so something is going on at a level I’m not conscious of, just as it used to be when I managed computer programs 250K FORTRAN lines long – so I haven’t lost it all.

Art vs Marketing

Chris: For a long time (ever since my adventures with traditional publishing), I’ve considered writing-as-art and writing-as-a-profession as two mutually exclusive endeavors. Of course, most of us try to balance somewhere in the middle. Are you ever worried about this balance? That is, are you ever worried you might write either something your audience won’t like or, conversely, something to please your audience instead of what you really intended to?

Alicia: Good question. And timely. The end of Netherworld – which a reader wouldn’t understand without the rest of it – is not tacked on. It has been set up in minute detail so it has to be – there is no other solution.

I fought that when I was planning and plotting and writing snippets and an awful first draft (designed only to make sure I could get from beginning to end on the plot stepping stones). I wanted it to have the feeling for the reader coming at it for the first or the n-th time that it was inevitable. That there was no way out of the morass but the one I left a little higher than the mud.

I think I learned that from Dorothy L. Sayers – in what she developed for her detective, Lord Peter Wimsey. Some of the final stories are over the top, too mannered for many readers – and yet, the feeling at the end is inevitability: it couldn’t have ended any other way. Maybe that only hits certain of her readers; if so, I’m glad to have been one.

And the end of the third volume of Pride’s Children – working title Limbo (or Limbo & Paradise) – must be the same: no other solution possible, even with the potential loose ends. I’m not a fan of the ambiguous ending – I consider that the failure of the author. After going along for the ride, I want a reader to have certainty. As the writer does (I’m of the class of writer who writes for herself). Especially since life isn’t that way, or not for long. Because life isn’t certain, we need our touchstones.

A Talk with Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt: “The Future of Poetry”

Chris: Matthew Arnold famously (and missing the mark, for now) claimed “The future of poetry is immense, because in poetry, where it is worthy of its high destinies, our race, as time goes on, will find an ever surer and surer stay.” If we interpret “poetry” to include literature in general, how do you see the future of literature? Are you optimistic or pessimistic?

Alicia: Hugely optimistic, even in the age of so-called Artificial Intelligence. Humans have this one – and the humans who do it have to put the work in and take the risks of not succeeding. The stories will simply get more complex – and the writers will still have to provide the path through.

Chris: Let’s consider something a bit lighter for the end – though I’ll still add disturbing tints; I can’t help it: Assume that a thousand years from now the human civilization is destroyed. Only ruins exist, rapidly consumed by Nature. A small alien spacecraft arrives and its crew discovers some paperbacks among the debris. They understand the significance and would like to take all of them back to their home planet, but they can’t; they only have room for 3 of them. Which ones would you advise them to take and why?

Alicia: I’ll have to be a bit facetious – I don’t know what the future will write in those 1000 years – Dune, Jane Eyre, On The Beach. Or maybe substitute A Canticle for Leibowitz for one of them? If they insist on taking paper – because electrons take so little space.

Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt: Useful Links

I don't show you ads or newsletter pop-ups; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?