January 10, 2018

Writing and Memory: Why It Is Important for Authors

I have talked in the past about nostalgia and reminiscence, and in this article I will emphasize the role of writing and memory in the context of writing fiction.

Many people are under the impression fiction is a process where you just “come up with things”, as if from thin air. This is inaccurate. Deep down, writing fiction is about telling a truth (often a secret or unpleasant one) in a different way.

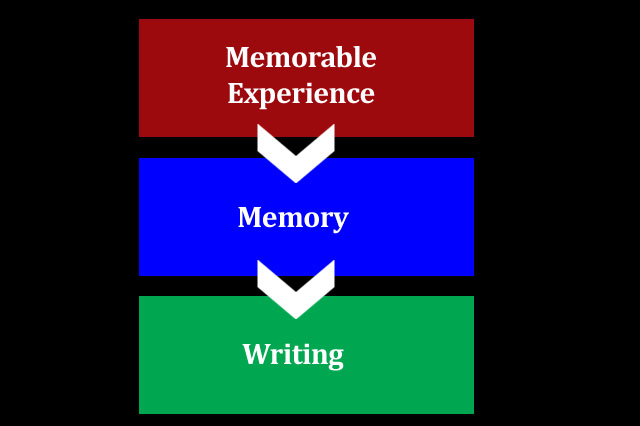

And so, experiencing becomes an operative element: before you write you must experience. Writing and memory, therefore, go hand-in-hand. The diagram below should give you a quick idea.

The term “memorable” is important. A memorable experience is not only easier to remember but also more valuable to remember. Of course this is an entirely subjective matter, and a skillful writer is precisely one that can turn a seemingly mundane experience into a momentous narrative chunk.

However, generally speaking, great novels materialize not because you remember what you ate last week, but because you remember how you felt on your first day at school. In this post I will show you the connection between creativity, writing, and memory. I will also give you 5 concrete tips that will help you become a better fiction writer by training your writing memory.

Writing and Memory: The Recollection of Moments

I mentioned in the previous section that great books are born because you remember how you felt on your first day at school – to name one example. Did you notice the emphasis? It’s not as important to remember the memorable experience itself, as it is to recall its affect.

In other words, it’s not really that important to remember any factual details about the experience, as long as you remember the way it made you feel; the kind of thoughts it inspired, the way it perhaps made you understand something.

Remember, we’re discussing about writing and memory in the process of writing fiction. Conversely, if we were talking about writing non-fiction (or journalism), then obviously facts should take precedent (unless if fake news is your thing!)

As the graph above shows, there is a linkage between memorable experience, memory, and writing. There are some further elements to take into consideration, so let’s make a list with all of them. Essentially, we’re expanding on the graph above.

Memorable Experience > Strong Affect > Mental Anchor > Memory > Recalling Affect > Writing > Manipulating Experience

To elaborate on the matter, I’ll use an example many of us could relate to.

I’ll never forget my first day at school. How could I, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing [Memorable Experience]. I remember how scared I was, how anxious to make a good impression [Strong Affect]. I think the uniqueness of this fear is what makes me remember the whole thing so vividly, it’s like a trauma of some sort [Mental Anchor]! Recently I’ve been thinking a lot about my first day at school [Memory], precisely because I remember how it felt [Recalling Affect]. I decided to write a short story about it [Writing], only I’ll have the kid be fearless and nonchalant [Manipulating Experience]. It’ll be fun!

Can You Train Your Writing Memory?

Often people ask whether you’re born one thing or you become it. For example, one may ask “Are writers born or made?“

There is no direct answer to that, not in a black-and-white way that people would like it to be. Some people might remember more easily because of their genetic code (disclaimer: I’m not qualified to make such a claim, I’m only speculating).

Others might have a vivid imagination in their DNA (ditto). I can assure you of one thing however: Virtually everyone gets better with practice, training, and experience. And writing and memory are two things you can train to cooperate together more efficiently.

OK, so how exactly Do You Train Your Brain to Remember Events?

Here’s the secret: creation, writing and memory are three facets of the same essence. It all boils down to experiencing; particularly, its connection to time and the present moment.

In more detail, memory is the tool that actually allows you to experience. Think of it like this: if there was some odd defect in your brain that erased your memory every passing second, could you experience anything at all? Could you see a movie, enjoy a meal, have sex, or go to the museum? The answer must be no. Memory is what allows you to have a concept of experiencing.

As for creation (which in our context of being an author uses writing as its tool), that serves the purpose of re-membering the experience. Creation puts the whole thing back together, using the bricks awaiting in the depths of your mind (including your unconscious). The end result might not be the same – indeed, it usually isn’t, deliberately so.

Once you realize that writing, creation and memory all coexist under the umbrella of experiencing, training your memory becomes easy. Here are 5 concrete tips for improving your creative memory:

Give yourself writing tasks related to old experiences

Pick an event from your childhood, even if you don’t remember it well, and write a short story about it. Don’t be preoccupied with practical details – remembering the color of your then-new shoes doesn’t matter; what does matter is the way you felt when, say, you stepped into mud and they got all dirty.Pick a quiet moment (I know…) and daydream about a past event

It can be before you fall asleep in the evening, though the time I would pick would be during a hot, sunny Sunday afternoon; perhaps after a greasy lunch, when you feel a bit drowsy. Go to bed, lie down, and close your eyes. Start recalling all the sunny afternoons of your childhood, then pick one that is memorable for whatever reason. It could be an afternoon you went with a neighborhood kid to explore a nearby abandoned house. Remember as many details as you can – sights, sounds, smells, surfaces – but mostly remember how you felt. Replay the events, changing details if you want.-

Start a List with All the People You Know

Writing such a list sounds momentous, but remember that you don’t have to actually finish writing it. You only need to start. Divide it into sections, starting from the oldest areas of your life: pre-school, school, perhaps a place you spent some childhood summers, etc. Then list as many names as you can remember, together with a short description; whatever you can remember. For example, an entry could look something like this: “John Smith; first-grade kid with red hair; he had a blue Hello Kitty wristwatch; we made fun of him; I felt bad about it”. Keep a Dream Journal

This might surprise or confuse you a bit. You might wonder what a dream journal has to do with writing and memory. Perhaps you wonder “why not keep a regular journal”. Well, if you want to, feel free of course. But a dream journal is much more useful for two reasons: a) it really pushes your mind to remember (have you noticed how rapidly we forget a dream as we wake up and the day advances?); b) it really trains you to remember affect – that is, feelings, emotions, and states of mind. Keeping a dream journal trains your writing brain to put words in experiences that by nature are not easy to describe (dreams, that is). Try it!-

Write Meta-Experience Texts

OK, this I need to explain a bit. But don’t worry, it’s not as hard or technical as it might sound. When I say that you should write meta-experience texts to improve your writing and memory, I mean this: write texts that reflect not only on the experience, but on your having the experience. In other words, give yourself little writing exercises that make you ponder on a memorable experience, on the fact that you had the experience, and on your remembering the experience today. For even greater depth, you can even ponder on your having the experience in the past with the future knowledge of having had the experience (this is easier to understand if you’ve read my text on the timelessness of experience). Here’s a quick example:When I was ten, I fell from my bike and broke my fingers [memorable experience]. I was scared in the following days, thinking that the fingers would heal so that they’re not straight [had the experience]. Well, I know now that it was a bit silly, but hey, when you’re a kid your priorities are different [remembering the experience]. I wonder how I would’ve felt that morning when they put the cast, if I knew that twenty years later I’d look back and laugh at myself [having had the experience].

Creativity, Writing and Memory: Conclusions

A good author of fiction is one who can skillfully translate experiences into words. To put words into abstractness, that’s the writer’s skill.

And in order to create – or recreate – a writer must have a deep sense of experience. This comes with good memory. Writing and memory are, really, two sides of the same coin that is experience.

The reason some people write more engaging novels than others is because they have learned to remember better. When I read a book I can usually tell whether the author wrote a certain scene as a result of remembering the affect of a past memory. Those are the best-written scenes, you need to have as many of those as possible.

I would invite you to consider Argentinian prolific writer César Aira’s insight that writing from memory actually sucks, because that’s what everybody did, and we need a renewal in literature. Thus, he proposes we write from objects. It is more clearly stated in one of his travel books, a tiny one, but I forgot its title. I’ll come back to it later and bring in more details, but I’ve been instinctively doing what he proposed some ten years before reading it. I guess I’m on some curious tracks.

I would probably need a wider context to properly understand what he means, but I wonder (feel free to correct me) whether he advocated a non-fact-based approach to storytelling. I would certainly agree with that, not only because memory is unreliable but also, in purely fictional terms, “writing from memory” (as in, recalling and narrating events) really does suck. I can’t stand writers such as Hemingway, for instance, who is arguably a good example of what I could term event-based literature.

My own take – as I hope it came through this post – is that we should be focusing on memory in the sense of memorable events and their associated emotive responses. To me, literature can be artistically meaningful only as so far as it instigates an emotive response. A book (a chapter; a scene) could make you feel solidarity, empathy, or that you belong. Or, it could disturb you, sicken you, offend you. But it has to make you feel something, otherwise it has failed.

While we’re at it, I’d put my money on the latter category. Literature that is affirmative (rather than disrupting) has less potential to instigate a change.

Feel free to supply more details later, once you find the additional resources, as you mentioned!

I have not found the book for I have not searched. Daily chores are killing me. But, yes, he criticizes Hemingway too, as an example of memory-centered writing. He compliments Melville’s Moby Dick on the other hand.