March 10, 2020

Affect in Writing: A Way of Feeling

If you searched Home for Fiction for the term “affective power”, you’d discover tons of results. I have referred to the concept of affect in writing in many of my posts – “Sounds in Literature”, “Writing and Reading Symbolism”, and “Narrative Exposition”, to name three.

I now finally decided to write a proper post about it, for two reasons: Firstly, it’s important to speak a bit more analytically about something I use so often. Secondly, I realized that some of my more academically inclined readers might think I make some claim to Affect Theory.

Let’s clear this latter part right away: Although perhaps some accidental commonalities might exist, the way I use the concept of affect has absolutely no connection to affect theory.

Rather, I deploy the concept of affect in writing to refer to emotions, thoughts, and states of mind. I’ll open up the concept in more detail, also explaining i) why it’s important for writers; ii) how to use it in your fiction.

Affect in Writing: The Basic Definitions

As I mentioned in the introduction and in other posts, affect in writing is an expression involving emotions, thoughts, and states of mind.

In more detail, you can think of affect as the background behind the plot. If character A does thing B, there is an instance of affect behind it.

At this point, I need to emphasize a crucial point.

Affect is about both what comes before this action (“thing B”) and what comes after it. It’s both the emotions, thoughts, and states of mind leading character A to doing thing B, as well as the emotions, thoughts, and states of mind occurring after thing B.

You could call the first part “motivation”, “drive”, or something similar, but it would be misleading. The reason? Affect is not an entirely conscious process.

To use a simple example, imagine an athlete practicing for an event. His motivation is to perform well in the event and, say, win a prize or secure a sponsorship. But affect describes all his insecurities, all his vices, the accumulation of all his experiences that have placed him in that particular place, at that particular time.

And so, this athlete might be afraid of success, and he subconsciously sabotages himself; he might be an egoist, and he subconsciously deludes himself into believing he doesn’t need much practice; perhaps he might be affected by a childhood memory or a dream, and he subconsciously finds the strength he didn’t know he had.

Now, let’s see why affect is important and how to use it.

Why Affect Is Important

Art is not about describing events; it’s about describing how these events make us feel.

Classics such as Dracula aren’t popular and… well, undead, because they talk about vampires or have vivid descriptions. Rather, it’s because their author managed – mostly subconsciously – to tap into a cultural moment. The Gothic is a way of talking about what cannot be talked about.

The genre of your novel doesn’t matter. You might be writing literary fiction or romance, horror or poetry. Affect is there. Your characters do all kinds of stuff, but the real importance lies not in what they do but in why they do it and how it makes them feel.

Because, ultimately, this whole process is what makes your readers feel, too.

Literature is not about creating fictional histories, in a sort of linear, point-A-to-point-B kind of thing. Literature is about creating meaning.

And you can become a better writer only by paying attention to the affective power of your narrative – how you treat emotions, thoughts, and states of mind.

How to Use Affect

So, how can you use affect in your writing?

Remember my post on literature being more than a sum of its parts? Here’s what I said there:

When you read book A, your mood that day is introducing bias. So does whether you read book B during a sunny summer weekend or in a rainy November evening.

Bias is good, when it comes to audience reception.

Bias is what facilitates feelings and an emotional response. You can’t have art without an emotional response.

Effectively, bias is the measuring stick that helps us gauge (not to mention create) meaning.

In order to increase the affective power of your narrative, you must understand your personal bias as a writer and embrace it.

In plain English, don’t treat your narrative objectively, because it can’t be. We all carry our personal ideologies with us, whether we admit it or not. Each one of us is part hero, part coward; part good, part evil.

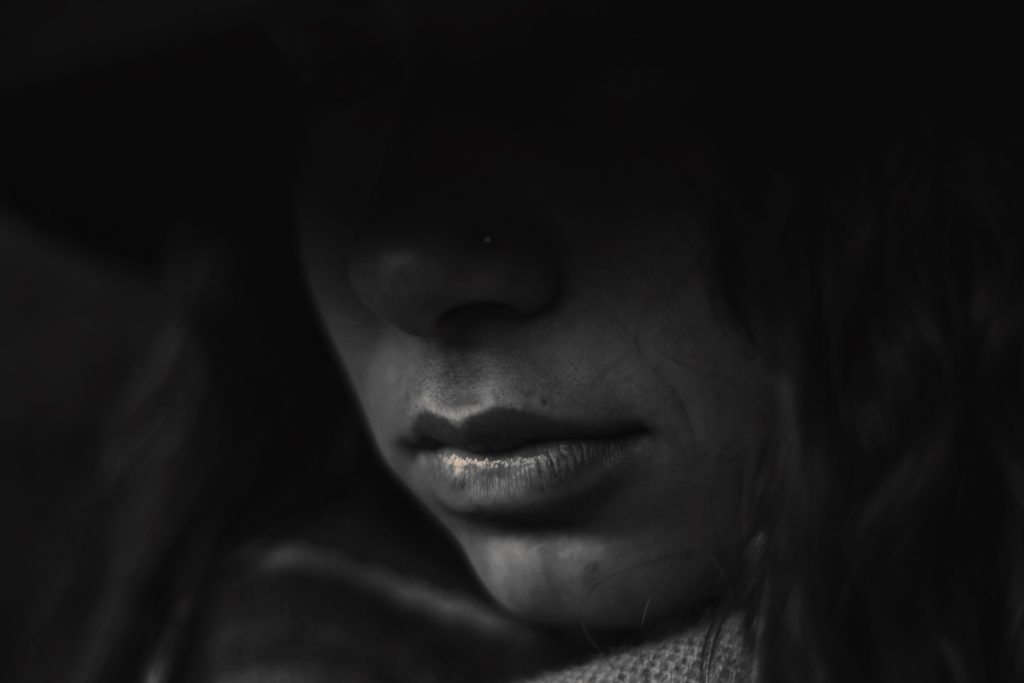

Sometimes we hide in the shadows, sometimes we broadcast to the whole world – every now and then with unintended consequences, but that’s another story.

The point is, you must put yourself in that narrativeIt is important to understand what "put yourself in that narrative really means", as there is a crucial difference between experience and experiencing. See the comment section for more information.. Most poor-quality books I’ve seen fail for this simple reason: Their authors leave out themselves – their biases, their quirks, all their little insecurities and fears that make us humans.

To paraphrase the incomparable Bill Hicks, write from your fucking heart.

Affect in Writing Is about What You Cannot See

Just in case you didn’t know, here’s some news: All plots have already been devised, all stories have been told. There’s nothing new under the proverbial sun, it’s only a matter of showing something new in terms of how and why something happens.

To be sure, it’s not easy. This is particularly the case for genre writers, who must balance between originality and audience expectations.

Ultimately, however, affect in writing is about showing the unseen. Quality literature – as opposed to books produced for monetary benefits – might offend you, scare you, or make you feel sad. It might make you feel good or it might make you feel bad.

But it has to make you feel.

I don't show you ads or newsletter pop-ups; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?