May 2, 2022

Experience and Memory: a Problematic Relationship

It’s impossible to experience without memory. Think about it: If you had no memory beyond the immediate, ever-ghostly “now”, how could you remember how a sunset looked like? How could you remember your first kiss, or some important achievement?

Moreover, it’s not only experiencing that, without memory, would suffer. Learning would be difficult if not impossible. Much of what constitutes our humanity would be absent.

And yet, there’s something problematic about the coexistence of experience and memory. I’m of course referring to the fact that memory taints the experience it’s supposed to help us remember.

We often think we remember things very well, very accurately, maintaining an objective view to their real essence. As the perceptive, thinking reader that you are, I’m sure you’ve discovered many problems in the sentence above.

The truth is, we don’t remember things all that well, not very accurately, and it’s quite by definition that we can’t hold an objective view, let alone to the “real essence” of things – good luck defining that, especially for emotions, thoughts, and states of mind.

As I’ve said before, memory is crucial for writing – either fiction or nonfiction. So, how do we go about resolving the paradoxical coexistence between experience and memory?

Experience and Memory: Why It’s a Problem

The disconnect between experience and memory is a problem when you want to construct an argument. “Back when I was a kid, life was easier. Therefore, things are becoming worse”.

The example is perhaps a little simplistic (though its core dynamics would be the same in more complex cases, too), but it conveys the issue. The problematic aspects of memory muddle our ability to reach proper conclusions.

Indeed, many of the fallacies you encounter – and much of the ignorance – are likely a result of people’s inability to differentiate between their memory of an event and the event itself; between memory and experience, in a way.

Though memorable experiences help your creativity and imagination, there is something deeply problematic about memory. Essentially, what memory does is that it acts as an amplifier of experience.

Now, why is that a problem?

Beyond Perception: The Problem of Induction

Just before we go into perception and induction (and why they’re relevant to the topic of experience and memory), allow me to draw on my music interests and complete the amplifier metaphor.

I have an Orange Crush Bass amp for playing at home. It’s small, it’s cute, it has sufficient juice. It also begins to produce distorted sound pretty rapidly (i.e. as soon as you crank up the volume a bit). It’s a poor amp for those wanting to showcase how a bass “really sounds like” (I let you ponder on the problematic nature of this) at a high volume.

The way a bass amplifier becomes distorted with volume, an “experience amplifier” – memory – becomes distorted with time. It’s a case of a trade-off of accuracy for having access to the experience at all.

The thing is, our experiences aren’t accurate in the first place. So let’s add induction into the mix.

In philosophy, inductive reasoning involves making observations and then reaching general conclusions. It’s an intuitively very solid strategy, and indeed often right. Both facts make it insidious.

The Turkey that Got It Wrong

The example is famous, you might have heard it. A turkey finds itself in a farm. It’s scared, but there is food in the morning. Then, more food in the evening, and then some more in the morning. The turkey, wanting to make accurate observations, takes careful notes.

On every day of the week, without exception, there is food. The turkey thinks it ought to account for other factors, such as the weather. But there is food whether it rains or not, in the cold mornings of April as well as the warm afternoons of June. The turkey wants to be really diligent in its observations, so it continues to take everything into consideration.

At some point in late October, after months of painstaking observations, the turkey finally decides that it has enough evidence: The farmer is benign, the farm is a good place, and nothing bad will happen.

Well, we know how this ends…

Memory Amplifies Experiences by Distorting Them

What induction and the hapless turkey show us is that observation is problematic to begin with. Memory, then, makes it worse by further amplifying the distortion.

We tend to remember very happy details – or the extremely traumatic. We generally ignore those in the middle, because our brains would become overwhelmed. As a result, if nothing traumatic has happened to us in a given past, we only remember the very happy things and, more often than not, we construct a flawed image of how life “really was”.

My bass amp distorts the sound a lot, rapidly.

The thing is, that’s how I like it!

Experience and Memory: Why It’s not a Problem

If a bass amp distorts easily, that means it’s awesome for my kind of music: grungy, punchy, dirty rock, doom, and metal. The amp takes the emotion and amplifies it, letting go of accuracy/clarity.

In the same way, working with memory of experiences, we can get awesome affect-based material for writing that might not be accurate. In other words, we give up on the illusion of facts in order to have access to emotions, thoughts, and states of mind.

Fiction doesn’t work with facts; it works with affect.

Moreover, there’s another element in all this: When I mentioned “the illusion of facts” above, I’m not only referring to our inability to accurately recall “how something ‘really’ was”. Rather, I’d argue that facts are illusory always.

There Are no Facts; Only Affect

Fair enough, we can (somewhat) agree that we share a common “out there” reality, that our senses are triggered by similar stimuli, and that we recreate some sort of common picture (literally and figuratively speaking) of these stimuli.

But what is “reality”?

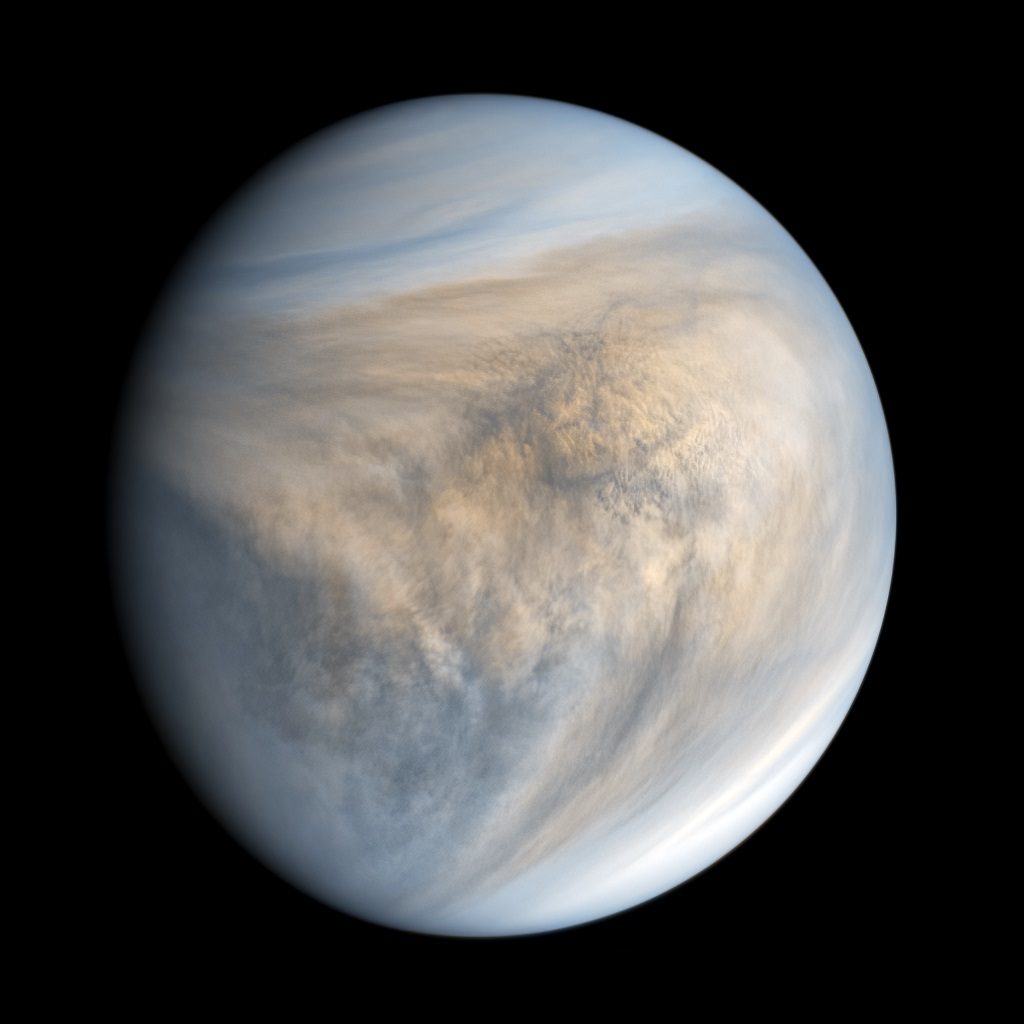

Here are three images of Venus, in visual, ultraviolet, and visual-ultraviolet composite wavelengths. So, which one is “the way it really looks like”?

In reality (no pun intended), it all depends. It depends on how it makes you feel – which is a factor of what day it is, what mood you’re in, what the weather looks like, and whether you’ve had your morning coffee yet or not.

I don't show you ads, newsletter pop-ups, or buttons for disgusting social media; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?

(If you'd like to see what exactly you're supporting, read my creative manifesto).