August 1, 2022

Authors Talk: Mikhaeyla Kopievsky

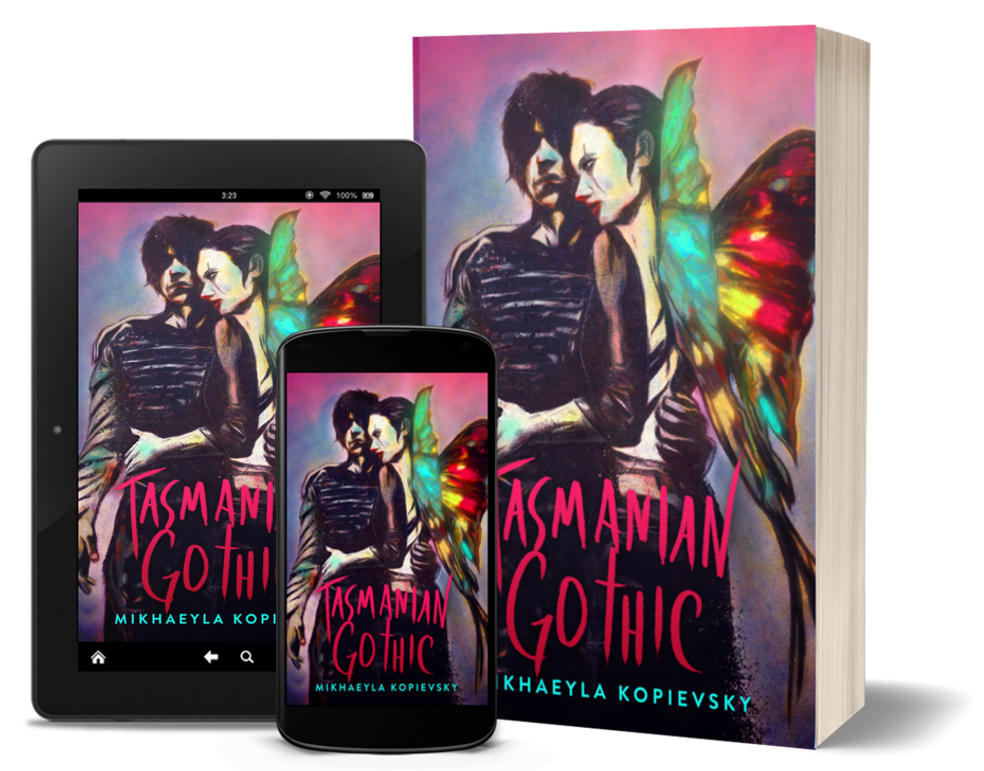

Another “Authors Talk” post. You can think of it as an author interview and, indeed, that is the name of the blog category. However, I prefer to see it as a friendly chat between fellow authors. Today I’m having this virtual discussion with Mikhaeyla Kopievsky, author of Tasmanian Gothic. A list of useful links to Mikhaeyla’s work can be found at the end of this post.

Image used with the author’s permission.

A Chat with Mikhaeyla Kopievsky: Tasmanian Gothic

Chris: As a first thing, I think it’s important to talk a bit about Tasmanian Gothic. As a writer, I know all too well how difficult it is to tell someone “what the book is about” (personally, I hate this question). I also have a theory on why it’s so difficult. With this in mind, instead of asking you what the book is about, I’d ask you to talk a bit about what the book feels like. What can a reader – one that knows little or nothing about your work – should expect in terms of affective impact?

Mikhaeyla: I love this question – mostly because what I love about stories (and what resonates and stays with me, long after I forget the words, the plot, and (sometimes) even the characters), is the mood. I like to say that I dream in colors – and reading (or devouring any story) is a similar experience – there’s a synesthesia about it; the story, the conflicts, the mood, the tone, the voice – it all creates a color or a particular kaleidoscope of emotion.

Tasmanian Gothic feels dark and twisty – it has the oppressive built environment, the lush and mysterious natural environment, the obvious and hidden terrors, the old and new secrets, and the deceptions and betrayals. There’s an urgency to the story, and a sometimes-quiet, sometime-thunderous desperation. But that darkness is also splashed with bright colors – the gypsy quarter, the summer solstice festival in a mutant enclave, the carnival border town. And it has softer highlights – vulnerabilities are revealed and genuine connections are formed.

If I’ve succeeded as an author, readers should come away from Tasmanian Gothic feeling like they’ve experienced a Perdido Street Station x God’s War x Frankenstein x Annihilation mashup of weird, dark, and exhilarating terror fused with a high-stakes road trip across a dystopian landscape, a gothic romance (with all its dangers and deceptions), and a subtle commentary on identity and prejudice.

Southern Gothic Tropes

Chris: In one of the emails we exchanged, discussing Southern Gothic, I suggested that Tasmanian Gothic might fit the profile. That is, Tasmanian Gothic might draw on similar tropes and motifs. Though literary criticism has to some extent explored Australian literature (perhaps particularly from postcolonial perspectives), I do confess my ignorance regarding Tasmanian narratives. In which ways would you say Tasmania has interesting literary things to share with the rest of the world? What, in your opinion, is unique about Tasmania in terms of literary dynamics?

Mikhaeyla: It’s interesting because Tasmanian Gothic shares the name of a whole sub-genre of Gothic fiction. When I decided on the title, I was acutely aware of how it would boldly announce this story as part of that sub-genre, despite (as a post-apocalyptic science fiction story) also rewriting key parts of it. Tasmanian Gothic as a genre, is very similar to Southern Gothic – the post-colonial history, the sense of place, the isolation and confinement, and the commentary on class and power indifferences.

Tasmania is a small island of the south coast of the Australian mainland – it literally is a place at the bottom of the world, surrounded on all sides by a raging, cold, and unforgiving sea. Its history – as a site of European colonization and its function as a penal colony – is also quite dark and brutal. When you add that unforgiving location and dark history to a wild and sparsely populated landscape – well, it’s ripe for Gothic imaginings.

I think the “sparsely populated” aspect is a really interesting one, and a key reason why Australian horror – whether the straight up psycho-suspense-thriller of Wolf Creek, the post-apocalyptic, dystopian nightmare of Mad Max, or the more broody, twisty, unsettling horror of Picnic at Hanging Rock—is such an enduring force. In all of these stories, there is a palpable, almost oppressive sense of place. Locations become characters, and the story is as much a conflict between characters as it is between characters and their environment.

In Tasmanian Gothic, I take inspiration from all of these stories – the dark, wild, brooding Gothic environment of Tasmania, the dystopian and post-apocalyptic road trip, and the horror and terror that comes not from supernatural elements but the evil in humankind.

Utopias and Dystopias

Chris: The line separating literary dystopias from utopias isn’t always quite clear, and utopias often degenerate into dystopias. I’ve always considered this temporal relation intriguing. As for post-apocalyptic settings, there is an even stronger temporal element (duh, the post- prefix should be a hint). A rather obvious guess regarding the popularity of such narratives is that we’d like to experience the what-ifs and – on a social level – perhaps do something to avert such disasters.

In your opinion, can post-apocalyptic narratives serve such a role? Does literature and art in general even have a “function” of this sort? Personally, I’m a bit reluctant to assign functions to art, because that would imply a conscious goal, an agency of some sort, which feels partly contradicting. I’d be very interested in hearing your opinion, since this is directly relevant to your work.

Mikhaeyla: I completely agree. And I’m a big fan of these contradictory/paradoxical explorations. My earlier novels, part of a dystopian trilogy (Divided Elements) also explores this – they take place in a future, post-apocalyptic Paris in its next “golden age” – except not everyone is happy with the status quo, and resistance is threatening to destabilize the new world order.

The novels, (hypocritically, as they are marketed as dystopian), are critiques of the utopia and dystopia – life is messy, humans are messy; there are no straight lines or hard boundaries or objective truths that define humanity. There is no right path to the perfect human existence – there can be no one path, because humanity is not made up of one type of person. We are many, and we are diverse. What I will die protecting, you will die dismantling. And therein lies its beauty and its tragedy.

Similarly with the post-apocalyptic genre. My favorite thing about writing this genre is, for all the “post” nuances, it’s actually a commentary about today’s society. It’s projected as the future, but you can see reflections of that fictional world in today’s flaws and horrors. In this way, I don’t think literature and art serve a kind of prophetical/advance-warning function, as much as they serve a function of reflecting (and amplifying?) the darker parts of the world that already exist.

People like to think that George Orwell predicted the future with 1984, but they fail to recognize that the same dystopian elements of propaganda, gaslighting, and rewriting history, were key elements of the world he was living in at the time of writing it. It’s not about averting these dystopian horrors as much as it is about challenging their current existence (and maybe halting their trajectory towards more devastating consequences?).

A Chat with Mikhaeyla Kopievsky: Writing and Art

Chris: Something that troubles me is the way writing expands in several directions that are at least partly (and sometimes entirely) contradicting. For instance, to me it feels being an artist and being a writer – that is, caring about the art versus caring about marketing, sales, and a career – are two separate things, and most of us struggle to find the balance between them. Similar dilemmas might also arise from the influence of literary criticism and possible pressures, either personal/ethical or societal/career-wise. Ultimately, what is writing to you? Why do you write? And how do you deal with possible inner conflicts, either of the sort described above or other?

Mikhaeyla: I think the democratization of the literary industry (ugh, those two words should never be together) and the advent of self-publishing has been an interesting development in this sense. On a side note, I really enjoyed your posts about mediocrity, and I think it is (maybe tangentially) related – we now live in a world where anyone can capitalize on their art.

This can be good – niche works, which would never attract traditional sponsorship because their target audience is too specialized, can still be published; high-risk, experimental works that have no guaranteed market success can be published; cross-genre, multi-genre, slipstream, hard-to-define, genre-defying works that have no clear audience or market can be published.

It can also be bad – the marketplace is flooded with works that have no objective threshold or minimum level of “artistry” to vet their presence; the lack of market-driven demand creates a lopsided effect where books are no longer a conversation between author and reader, but a monologue dictated solely by the author.

Storytelling, at its core, has always been about connection. Good storytelling can expand, transplant, unravel, and reconstruct a person – their ideas, emotions, ideologies, perspectives. In some ways, the market (imperfect as it is) can help us understand that connection. If we agree that the market is just the manifestation of people’s desires (and the assigning of a dollar value to that desire), then we can understand that it holds some valuable information about what moves people, what inspires them, what enlivens them.

On the flip-side (as you yourself have pointed out in an earlier post), the marketplace is not only a demonstration of desires, but a manipulation of them. Sometimes people don’t know what they want or know what they’ll like, until they’re presented with it. Sometimes the market has to be supply-driven, sometimes it has to take a risk on what hasn’t been seen (or liked or demanded) before.

In this way, I tend to straddle the line a bit. I write the stories I want to write – without fear of favor of the market; but I also respect that my medium is one of communication and I want my stories to find a home in a reader’s subconscious. I write to share, to establish a dialogue, to contribute to the narrative and the sense-making of this world.

I’ve pursued traditional publishing, in the hope of reaching new readers (but also to gain validation that my work has value, objectively, as piece of art (which has a technical and cultural appreciation to it)). But I have no shame in independently publishing when the traditional marketplace has no place for my work. If I believe in its value, I’ll set it free. And I’ll do my best to market it so that it finds the readers that will be moved by it. There’s no point speaking eloquent words into the void; the transformative aspect of fiction is not only the writing, but in the receiving. It does the art no harm to think of its audience.

The Near Future of Reading and Writing

Chris: The central premise of one of my novels, Illiterary Fiction, is about a society where people have basically given up reading because they can’t be bothered. What are your thoughts on the state of reading and writing? Are we moving – perhaps insidiously – in a direction where reading more than a tweet will be considered too much of a hassle?

Mikhaeyla: I hope not. There is definitely a convenience with the “fast storytelling” of sound bites, tweets, and tiktoks (much like fast food), but I think people will never give up on reading long fiction altogether. Let’s face it – reading is not easy. We live in fast and over-subscribed times – too much to do, too many things to juggle, too little brain and emotional bandwidth left at the end of the day.

Reading takes time (much more time than watching a 30-second tiktok, let alone a 30-minute episode of the new Netflix drama). It also takes more focus – you can’t read and eat pizza at the same time, or read and scroll twitter, or read and knit a new scarf, or read and do anything else, really. Reading requires something of you, demands a certain level of attention and commitment – and that’s hard to come by these days. (Also why nailing the first sentence/paragraph/page is so crucial – you need to immerse readers as quickly as possible in your story so that the “effort” of reading becomes effortless and (shortly thereafter) completely invisible).

That said, I’ve been participating in a beautiful online community over on George Saunders’ substack. George is one of my literary heroes and, beyond that, is a gracious soul and generous teacher. In this community, which has become a kind of MFA for anyone and everyone, George has been reigniting not only a love for reading, but for reading slowly and deeply. We’ll spend weeks reading a ten-page short story. And it is glorious.

The joy, the enlightenment, the connection that comes from reading and sharing these stories has been immense. And it stems from the depth of the stories themselves – each presenting new layers to discover and unfold, layers that would have been missed on fast, cursory reads. And I think there’s a power in that. And a reaffirmation of the importance of literature. Yes, it takes more effort; but good things often do. While we all enjoy cheap escapism, there is something inside us that craves and seeks out nourishment. Longer fiction – with its challenging concepts, multi-faceted characters, and depth of layers – can give us that.

Mikhaeyla Kopievsky: Useful Links

You can purchase Tasmanian Gothic here:

Follow Mikhaeyla Kopievsky on bookbub or sign-up for her author newsletter for exclusive access to new releases, giveaways, and more. You can also check out her blog where she shares her writing process and publication journeys, discusses genre, and interviews other authors.

I don't show you ads, newsletter pop-ups, or buttons for disgusting social media; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?

(If you'd like to see what exactly you're supporting, read my creative manifesto).