March 20, 2023

How to Introduce Characters: Examples, Problems, and Genre

Whether you write short stories or novels, fantasy fiction or literary fiction, you have to deal with characters. Even experimental fiction needs some sort of characters. Is there an optimal way of introducing your characters to your audience?

This might feel like a deceptively simple thing. Surely, one might think, introducing characters can’t be that hard? Well, writing is as hard as you make it, in a way, but that’s beyond the point. Rather, our point in this post is to discover whether there is an optimal way of presenting your characters to your readers.

Obviously, the statement is rhetorical.

Of course there are more than one ways of introducing your characters to your audience, which automatically makes some of those ways “better” – and we’ll soon have to define that – and some “not so great”. Which means, as a writer you have a strong incentive to reflect on how you introduce your characters in your fiction.

That’s what I’m here for!

In this post I’ll show you – with examples – the different ways we can use to introduce the characters of our story. I’ll explain why some ways are “better” than others (and what that really means), though we’ll also take a look at some problem points; gray areas, if you like. Sneak preview: These have to do with the ever-lasting struggle to balance between genre and literary expression, between marketing and art.

The “Better” Way to Introduce Characters

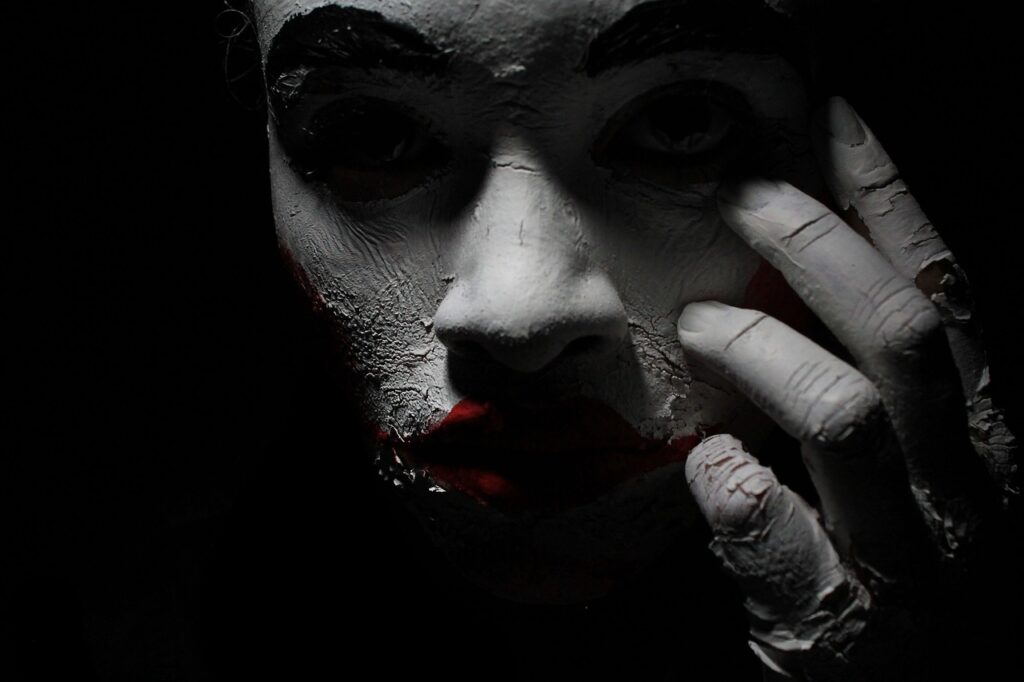

The caption of the photo above should give you an idea regarding what “better”, “best”, or “optimal” might imply in this context: The more supportive of your authorial aims the introduction of your characters is, the better. In other words, if your methodology of introducing your characters helps you achieve whatever it is you want to achieve, then it’s “good”.

This might sound like a truism of some sort, but it’s necessary to help us understand that introducing characters is, like everything else in literature, a matter of priorities.

And so, with the above in mind, the right thing to do when you introduce your characters is to do it in a way that supports the narrative at large.

How, you’ll rightly ask.

Once Again, the Power of Concepts

Starting with concepts is powerful because it allows you to connect the various aspects of your narrative in a coherent manner. Literature is a connection game, remember.

In simpler terms, an author’s job becomes far easier when they have a clear picture not only of the plot, the characters, the “what happens” – and even the “how it feels” – but also of how all these fit together.

For example, if you’re a science fiction author and you’ve paid a lot of attention to the world of your story, reflecting deeply on things such as the accuracy of the physics, the feasibility of the setting, and so on, but then you have a spell-casting wizard as a character, something is “wrong” – though we’ll come back to this in the conclusion.

Your characters need to be consistent with your narrative, that much should be obvious.

What perhaps is less obvious – and here’s where this post squeezes itself in – is that the way you introduce characters is part of this consistency.

Some Examples on How to Introduce Characters

Let’s begin with some examples that I’ll use to expand on the themes above. Once again I’ll rely on my own books, not out of vanity but because I know them intimately. In other words, I can precisely explain why I decided to introduce the characters the way I did.

Most of my fiction is available as an immediate free download – simply visit the Fiction page on the main site. And remember, you can also just email me and ask for a free, no-strings-attached (e.g. review etc.) digital copy of any of my books.

The Other Side of Dreams: Prioritizing “How It Feels”

And let’s start with The Other Side of Dreams:

To feel humiliated was an almost daily experience for him, the way other people try to decide between a cappuccino and a latte. Quite often he was made to feel that way through other people’s piercing stares – that penetrating gaze that burns “not welcome” on your mind like the pulsating red iron of a slave owner. The rest of the time he made sure to do the thinking for them: They look at me, he’d hear himself whisper like a scared mouse, quick, quick, look away, don’t let them see you seeing them.

But the worst shame came when he was alone with himself, trapped inside his mind which was trapped inside his body which was trapped inside his one-room apartment with the flaking walls and the leaky faucet. It came when he had to calculate whether he could afford all the ingredients needed for the bean soup, or when he tried to decide what would be more nutritious, a casserole without cheese or a risotto without any vegetables. Perhaps he ought to skip breakfast altogether, then it could work for another week. Sometimes he didn’t eat at all, to feed her instead and her special, destructive hunger.

She called him Ahmed, but that wasn’t his name – in actual fact, he didn’t possess his name either, as it had already been chosen by his father when the man was born

In a literary-fiction story revolving around concepts such as immiseration, societal alienation, psychological breakdown, and loss of control, I felt the most important part of introducing the protagonist was to show how it felt to be him – far more important than where he was, how he’d ended up there, and even why.

Illiterary Fiction: “Can You Introduce Characters in One Paragraph”?

That’s not any kind of challenge I gave myself, but after I had written the introduction, I discovered that the first paragraph indeed told us a lot about the protagonist:

The headlights of the cars intermix with the bright shop windows and flow in colorful rivers before his eyes. He’s waiting to cross the avenue, obeying the traffic light, mesmerized by the redness of the hand that orders him to stop. Or else what? He is too polite to discover. He’s also too polite to say anything to the teenagers making duckfaces while incessantly snapping photos with their cell phones.

Of course the full impact takes a few more paragraphs, but this first paragraph already places the protagonist in the context of being used to “playing by the book” – and suffering for it. At the same time, it also reveals the divide he will struggle with in the entire narrative: that between a sensitive, literary-minded as himself and the inane world around him.

The Perfect Gray: When It’s about Style

With The Perfect Gray, introducing a character is to some extent less about the character herself and more about the narrative style.

I sold my liberty today. The price was negotiated long and hard, though not by me. I was an active bystander, to be sure. Carefully and meticulously, with concentrated insouciance, I saw the men agreeing to the minute details of how that incorporeal concept was to be removed from my ghostly possession and be given to them, divided and chopped up according to their laws and whims.

My name is Hecate; it wasn’t chosen by me, but I’ve learned to like it. At the very least, I’ve become accustomed to it, reaching that cherished realization of passive acceptance. I’m neither young nor old – which would, I suppose, place me squarely in middle age, or what I’d like to think of as not-giving-a-shit age, if it weren’t a self-deluding lie.

I wrote The Perfect Gray with contradiction and conflict possessing central roles, also in the narrative style. I wanted the introduction to clearly reflect this.

Practical Tips on How to Introduce Characters

The main goal, as I said, is to introduce characters in a way that serves your particular authorial purposes. Obviously enough, the exact details will depend on that. But here’s a quick list for you to consider.

- What is the immediate thing you want to communicate about your character? A character might be brave or a coward, intelligent or dumb, practical or abstract, and plenty of other things. The more realistic a character, the more traits to consider. But you will need to prioritize and show the most crucial ones right away.

- Should you use dialogue or descriptions? Though there generally isn’t right or wrong in fiction, I find dialogue a problematic way of introducing a character. The reason is that dialogue with interjected prose (e.g. “he said and looked at Joe with anger in his eyes”) needs preexisting contextual information – I mean, how would you start a narrative using “he”, “Joe”, and “anger” in this example? Alternatively, you wouldn’t use any and opt for ambiguity, but that has its own problems – it would basically postpone introduction, delegating it to the prose following the dialogue.

- Is it, even about the character at all? As The Perfect Gray example above indicates, sometimes it’s more about introducing the narrative. That is, you can choose to postpone showing who the character really is, to prioritize showing what the narrative feels like. Of course, in most cases these two go hand in hand – at least in character-based narratives.

- Ultimately, to which extent is it about art and to which about marketing? This is a huge topic, so let’s take a look at it in its own section – which, fittingly perhaps, will also be the concluding one.

How to Introduce Characters: Problems and Gray Areas

The problems of introducing the characters of your novel boil down to the ever-present struggle that contaminates much of modern writing: Is it about art or sales?

These two are mutually exclusive, remember. Art is about divergence, making uncomfortable, asking to think. Sales are about similarity/relatability, pleasing, asking to like. Of course, the vast majority of writers try to balance somewhere in the middle.

And so, introducing characters also must take that into consideration, too. There are plenty of intriguing ways to begin a story, but some of them will manipulate your readers into thinking a certain way about your characters that might not be compatible with the genre you’re writing in. Even deciding how to name your character affects all this.

To put it plainly, introducing your protagonist as unequivocally malevolent (or stupid, naive, etc), manipulating your readers so that they hate that character, only later to start revealing nuances and things-aren’t-that-simples is (potentially, of course) solid artistically and risky marketing/genre-wise.

Lionel Shriver is a great example of that, parenthetically. But for every Lionel Shriver, there is a vast number of writers who failed in attracting buyers (assuming that was their goal) because they alienated them with the very same style.

So, where do you draw the line between art and marketing, black and white? Where do you find “the perfect gray”, if that’s what you’re after?

There are no easy answers, I’m afraid. Only the author can provide tentative answers, subject to reevaluation.

I don't show you ads or newsletter pop-ups; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?