October 30, 2023

Ember’s Disappearing Clothes: Unnecessary Diversions in Fiction

I’m sure this is one of those post titles I really need to explain. I mean, “unnecessary diversions in fiction” gives you at least some idea what the post will be about, but who the heck is Ember? And what do her disappearing clothes have to do with all this?

Ember is a character in the comic series Storm, drawn by Don Lawrence. In the non-English-speaking world she’s also known as Redhair, from the original Dutch “Roodhaar”. Storm was among my favorite childhood comics – together with Donald Duck. Don Lawrence was an incredible artist, and to me his work still is the reference point for realistic, affectively impactful art.

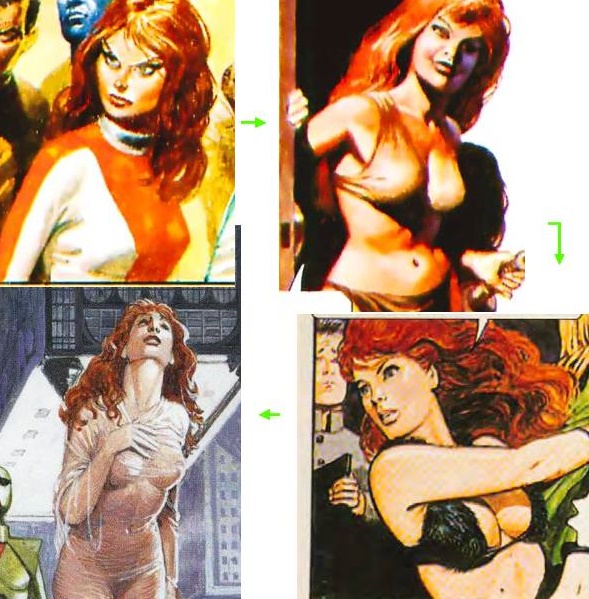

As a child, I only had the first ten or so Storm books – there have been something like thirty-plus in total, together with some spinoffs. I recently decided to search the net for the books I hadn’t read, and I did find them. It was a nostalgic trip – nostalgia is a trap – but I couldn’t help but notice something interesting: The more the stories progressed, the less… covered Ember became.

Are All Diversions in Fiction Unnecessary?

This seems like a crucial question to answer: Are all diversions in fiction unnecessary? Are there necessary diversions? And is fiction, then, necessarily a framework without diversions – when life does include them?

Before we proceed, perhaps I ought to attempt a definition of diversions in fiction. To me, a diversion in fiction is a departure from the main narrative flow. This can be a flashback, a secondary plot, the backstory of a character, and so on.

It becomes evident that diversions in fiction are very common – so they can’t all be bad, right?

Narrative Inevitability

The answer is obvious, but less obvious is perhaps the reason – which will also help us understand necessity: Diversions in fiction are unnecessary when they don’t serve narrative inevitability. A flashback “just because”, a secondary plot “to have more pages”, or the backstory of a character “because it’d be cool” are dangerously flirting with being unnecessary.

On the other hand, any diversion which is inevitable – because it explains something about the plot, reveals a character’s motivation, or even helps us understand the symbolic framework – is absolutely necessary.

So, are Ember’s disappearing clothes a necessary diversion?

“Hottest Comic Heroine” Is Narratively Avoidable

As I discovered on a Storm Wiki page on Ember, she was voted “hottest comic heroine”. It sounds cool, but remember: It doesn’t mean anything from a narrative perspective.

Instead, there is only one question here to answer: Is Ember’s losing her clothes justified by the narrative progression?

On the surface, the answer is “mostly not”. We could try to come up with ad hoc explanations – “it’s too hot”, “it’s easier to fight without clothes”, “I like to travel light” – but in all honesty such explanations don’t quite hold water. The only plausible explanation for Ember’s disappearing clothes is just because it looks nice – especially to the intended audience and the male gaze.

But is that not a good enough reason?

Diversions in Fiction: Aesthetics and Inevitability

A comic book consists of two parts: the text and the drawing. Whereas a narrative in the form of a novel or short story is only about the text – or is it? – with comic books things are more complex.

In a comic book like Storm, there is an element – albeit small – of a symbolic representation in the way characters are visually portrayed. To show Ember “fully clothed”, “partially clothed”, or “virtually naked” is an aesthetic decision, which in a comic book context makes it a narrative decision.

In other words, the way characters are visually depicted – including their clothes – is much more open to interpretative explanations in a comic book than it is in a novel – perhaps especially in a science-fiction/fantasy context. To put it plainly, some things can be drawn just for the heck of it.

What About Writing?

Diversions in fiction writing are harder to justify, precisely because the aesthetic value must be comprised in the text itself. In a sense, narrative pace suffers more in a novel than in a comic book because it’s a different medium, one requiring a lot more effort to portray the same amount of information.

Just look at Ember’s images above. What takes two seconds to process visually, would require whole paragraphs to convey in textual form. To put it simply, the borders of narrative inevitability move significantly in such a context.

Diversions in Fiction: a Literary Device of Sorts

Ultimately, perhaps we could think of diversions in fiction as another literary device – not unlike foreshadowing or irony. As such, it either serves the narrative and is necessary, or it doesn’t and is unnecessary.

Of course the trick then is to learn to recognize necessity. Is a secondary character’s childhood all that important for the conceptual framework of the novel? How about that flashback to that summer ten years ago?

If you have good, ready answers to such questions, it’s fairly likely such diversions are necessary. At the very least, they are not unnecessary. Like Ember’s disappearing clothes, the story could probably proceed without them. But having an additional layer – no pun intended – of meaning, albeit frail, is also not without value.

Can we have an addition of meaning post factum? After the literary work has been written and published, could it occur that an originally inconsequential (“just for the fun”) addition rendered the text more rich and complex (and compelling, even) for the reader, whilst originally it was not intended as such?

I’m sure literature is full of such examples, as a result of “imposing” (the word sounds more aggressive that it should) interpretations belonging to a different sociocultural context.

Goblin Market, for instance, has been interpreted in ways that Christina Rossetti almost certainly didn’t intend, but which surely enrich the text and help us understand it in ways she probably did. The assault of the goblins, for example, has been read in much more sexual terms than the pious Rossetti meant them, but in the context of feminism and a more general gender-based power imbalance, such readings make sense.

Still, you mentioned inconsequential additions. That would be an intriguing subcategory of the above indeed. I also wonder whether forwards, epilogues, subsequent-edition alterations would fit the profile.

I remember reading one novel -La Rotisserie de la Reine Pedauque” by Anatole France that had a lot of sub plots, yet it all added up to a whole.

I think in film , David Lynch does that

Haruki Murakami is also a repeat offender. I speculate he’s a so-called pantser, writing without any plan or cohesion, ending up with a lot of loose threads and dead ends.

Was it Chekhov I think who said that, if you show a gun in your play, you better have somebody killed with it at some point, or something of the sort. I don’t fully agree with that either – some things have meaning because of their absence – but as a reference to narrative necessity, it’s good to keep in mind.

Maybe a lot relies on the form. Peripatetic novels (or process oriented), or novels of initiation can accommodate different scenarios as part of the adventure. Anatole’s novel seems to be both. When a writer just rambles on from one thing to another without any continuity – perhaps that’s where it falls to pieces. Something like those B movies that start with an interesting scene, but then just goes from one random event to another without any rhyme or reason.

Interesting observation, you’re probably right about it. In this context, narrative branching (and even cul-de-sacs) would effectively become literally devices – which of course would render them narratively necessary. But yeah, there are also those “without any rhyme or reason” cases, aplenty!