May 15, 2018

Religion in A Christmas Carol

Note: the following article on religion in A Christmas Carol is a modified excerpt (pp. 112-115) from my doctoral dissertation, “Time is Everything with Him”: The Concept of the Eternal Now in Nineteenth-Century Gothic, which can be downloaded (for free) from the repository of the Tampere University Press. For a list of my other academic publications, see here.

You can also find an article about religion in Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

Religion in A Christmas Carol: a remarkably Secular Affair

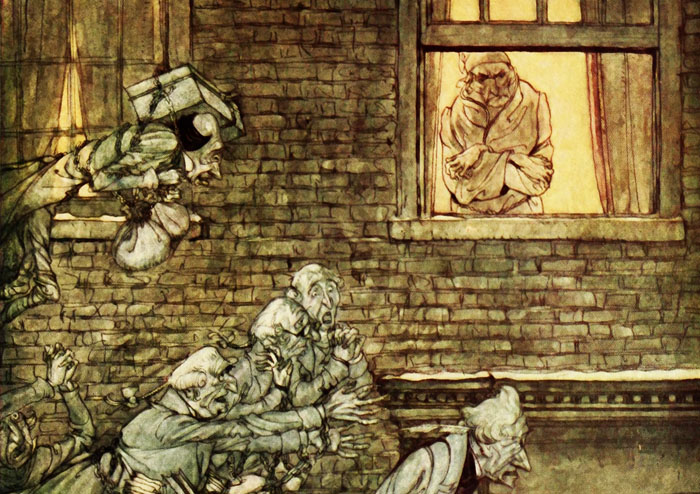

Although religion in A Christmas Carol is mostly absent, the text still creates a framework of otherness based on Scrooge’s background and, in particular, his possible Jewishness. His occupation as a moneylender and the fact that he does not celebrate Christmas would have been obvious characteristic markers of Jewish origins for that time. Such stereotypes were not uncommon in Dickens’s works at large.

In Oliver Twist, the character of Fagin is referred to as “the Jew” almost three hundred times and the novel abounds in descriptions “that directly link him to Judas Iscariot and even Satan” (Muller 2003, xxvii), with connotations of the classic depiction of the Wandering Jew also present (Felsenstein 1995, 241). The process of shifting from a racially motivated wariness – if not outright hostility – to an absolution has been suggested to exist within Dickens’s works, although not without controversy, as Grossman argues:

[T]his understanding of Dickens’ Jews elides how Dickens’ narrators engage the problem of narrating this racial and religious other. This elision has most obviously resulted in an institutionalized disregard for Dickens’ final 1867 revision of Oliver Twist, in which he only selectively deleted the term “the Jew”. (1996, 37; emphasis in the original)

Religion in A Christmas Carol: Some Hidden Elements

The intriguing aspect of A Christmas Carol in regard to depictions of Jewishness is of course the fact that Scrooge is never explicitly referred to as Jewish although, as mentioned, his occupation as a moneylender and his refraining from celebrating Christmas strongly suggest it. More tellingly, not only does he not celebrate Christmas being an old misanthrope, but he tells the Ghost of Christmas Present he has never seen him or his “brothers” ever before (Dickens 1994, 40), implying he has never celebrated Christmas, even as a child.

That would certainly be sense-making if Scrooge is of Jewish origin. Even his first name, Ebenezer, certainly alludes to Jewish origins – as does the first name of his deceased business partner, Jacob Marley (Grossman 1996, 50). At the same time, the description of Scrooge is also quite telling. He was “[h]ard and sharp as flint”, as “[t]he cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red” (Dickens 1994, 8).

Temporality and Religion in A Christmas Carol

In many ways, Scrooge is presented as a true Gothic monster, not only in terms of appearance but also temporally: a true undead, believed to be quasi-immortal (Dickens 1994, 59), a character that “frightened every one away from him” (Dickens 1994, 64). More broadly, Scrooge is presented as clearly an Other as he could possibly be, and this includes temporal elements.

The fact that he does not celebrate Christmas holds temporal implications, as he places himself outside the cultural markings of time and the calendar – to the point that “no children asked him what it was o’ clock, no man or woman ever once in all his life inquired the way to such and such a place” (Dickens 1994, 8). Scrooge is outside space-time, both culturally – that is, in terms of the Victorian Christian context – and, in the course of the story, also literally.

Religion and Temporality: A Textual Example

Characteristic is the scene between Scrooge and his nephew, after the former rejects the latter’s invitation to Christmas dinner. When his nephew asks Scrooge why he does not want to join him and his wife for dinner, the old miser replies with a question of his own: “Why did you get married?”. The young man’s reply comes naturally: “Because I fell in love”, which makes Scrooge grumpier still, “as if that were the only one thing in the world more ridiculous than a merry Christmas” (Dickens 1994, 10–11).

However, as Grossman argues, the exchange makes sense considering Scrooge’s possible Jewish origins. If Scrooge is indeed Jewish, then his nephew is also Jewish. For Scrooge, if his nephew celebrates Christmas, that is a consequence of his marrying a Christian woman (Grossman 1996, 50). For the old miser, however, the problem is not ethnic or religious. Rather, his is an issue of spatio-temporal inexistence.

Scrooge is all but completely isolated from society, and this lack of time and space reference becomes literally materialized – a rather typically Gothic device. After all, Scrooge’s isolation does not end in the deceptively jolly ending of the story. As Grossman argues, the only thing that has ultimately changed is Scrooge’s mood shifting; “depressive in the beginning, he is manic in the end”, and his peculiar jokes are still not a product of his desire to amuse others, but only himself:

His jokes, articulating the uneasy space between himself and society, reflect in their nervous releases how Scrooge’s isolation from the novel’s community is unbridgeable and, perhaps, partly unwritten. Perhaps because the possibility of Scrooge’s Jewishness troubles, but never enters, the narrator’s discourse, the narrative cannot fully resolve Scrooge’s predicament. (Grossman 1996, 51)

Jewish Temporality in A Christmas Carol

In temporal terms and in the context of Judaic cultural tradition, the birth of a new idea is not temporally placed in the future or the present in the sense most (Christian) Victorians would define it, but rather in “a radical reinterpretation of the past, which was not so much taken as past, but rather as part of the ever-living, redeemable present” (Hansen 2009, 114).

Jewish Temporality and Hegelianism

In some ways, Hansen’s formulation is Hegelian in its constituents: unlike the mainstream, linear Victorian time, what Hansen describes is a process of synthesis. The past (thesis) is not discarded in favor of the future (antithesis) but is rather placed in a framework of doubt and reinterpretation. It is finally incorporated into the new form (synthesis; the new thesis) that, crucially, is materialized through what Hansen refers to as the ever-living present.

In the context of religion in A Christmas Carol, this eternal now is distinctly transcendental, almost spiritual. Scrooge’s is a story of ostensible transformation, and the old man, panicked at the prospect of his future demise, is quick to pledge that he “will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future” (Dickens 1994, 70), certainly an explicit way of describing an all-inclusive eternal present.

Read more: Angelis, Christos. “Time is Everything with Him”: The Concept of the Eternal Now in Nineteenth-Century Gothic. Doctoral Dissertation. Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press, 2017. Available from the repository of the Tampere University Press.

Works Cited

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. London: Penguin Books, 1994.

Felsenstein, Frank. Anti-Semitic Stereotypes: A Paradigm of Otherness in English Popular Culture, 1660–1830. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 1995.

Grossman, Jonathan. “The Absent Jew in Dickens: Narrators in Oliver Twist, Our Mutual Friend, and A Christmas Carol”. Dickens Studies Annual. 24 (1996): 37–57.

Hansen, Jim. Terror and Irish Modernism: The Gothic Tradition from Burke to Beckett. NY: State University of New York Press, 2009.

Muller, Jill. Introduction. Oliver Twist. By Charles Dickens. New York, USA: Barnes & Noble Classics, 2003.

I don't show you ads or newsletter pop-ups; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?