May 22, 2023

Are Narrative Worlds Real? Reflections on Metaphysics

As a child, whenever I got emotionally affected watching a film or reading a story, my folks would try to console me saying “It’s not real, don’t worry”. That didn’t help at all. To me, narrative worlds were real, more real than reality itself. After all, fiction and reality are not antonyms.

When we talk about the reality of imaginary worlds – narrative worlds, in our case – the discussion seems moot. “Of course narrative worlds are not real”, any random observer would likely utter with – not misplaced – confidence.

After all, when you follow the characters of a video game, you can always save your progress and restore if something goes wrong. Similarly, when you read about a lonely female programmer plagued by indecision, her life never leaves the confines of the novel. You can’t meet that woman, her actions don’t dictate yours and can’t change the world.

Or… can they?

The Reality of A Christmas Carol

In Charles Dickens’s novella, Scrooge’s mind acts as a literal creator of worlds – with meta- hints concerning the process of reading:

For the priorly unemotional old man, the space-time travels offered by the ghosts do become more real than “reality”, in that they allow him to explore a previously dormant side of his self, that is his emotional response. In Scrooge’s current situation, this aspect of reality does indeed contain a vital function.…Memory is present, not only as the building block of this synthetic, omnijective reality, but also in its ability to reinterpret and reform future and past alike. Effectively, by employing the time-travel motif, A Christmas Carol emphasizes the mutability of memory and hence “reality”.

Angelis, Christos. “Time is Everything with Him”: The Concept of the Eternal Now in Nineteenth-Century Gothic. Doctoral Dissertation. Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press, 2017. Available from the repository of the Tampere University Press. pp. 153

In plain terms, A Christmas Carol portrays an example of an imaginary world that influences reality as a result of reinterpretating this reality. It does so within its own plot without a recourse to fiction. In other words, Scrooge doesn’t ostensibly change his ways because he reads a book, but because he faces a “higher-order” reality – not unlike some highly realistic virtual reality or, say, LSD-induced trip.

Nonetheless, the allusion is there: Narrative worlds are real, if they can change our understanding of reality.

Or not?

Narrative Worlds Are Real Insofar as Emotions Are

Let’s ask ourselves another question first: Are emotions real?

To me, this seems like a crucial element in the attempt to gauge whether narrative worlds are real. If emotions are real, narrative worlds are also real. This would be in accordance with the notion that a narrative world event – a child becoming emotional because of a film or a fictional character like Scrooge because of some… Victorian version of virtual reality – can influence the real world.

As I see it, the answer to this question is, yes, emotions are real. However, self-evidently, emotions are also incorporeal. This adds a footnote to the “reality” of emotions and narrative worlds alike.

The truth is, we are surrounded by concepts and feelings, states and ideas, that are all real in some way we define reality, and yet not in some other way.

The Metaphysics of the Past and the Connection to the Physical World

Is the past real?

After all, if the past is reconstructed by memory, it is (very) likely to be inaccurate – to some extent at least. The more common the memory and the more the physical evidence, the higher the accuracy.

Nobody in their right mind would claim ancient Egyptians didn’t actually exist and didn’t build the pyramids, but it is not beyond the realm of possibility that a scary event of my childhood was nothing more than a dream. I’m fairly certain it wasn’t, but – believe it or not – I’m less confident about that reality than that of ancient Egypt.

An important element of the way we understand reality is precisely this exchange between concepts and physical existence. In the example above, we have immense confidence in the reality of the past that we call “ancient Egypt” because of the vast number of physical evidence across many categories and verified by many different disciplines.

Physical reality isn’t unproblematic – just recall the ship of Theseus. But it has a unique claim to “real” reality that is less complicated than emotions, ideas, and thoughts.

The Exchange Between Matter, Concepts, and Worlds

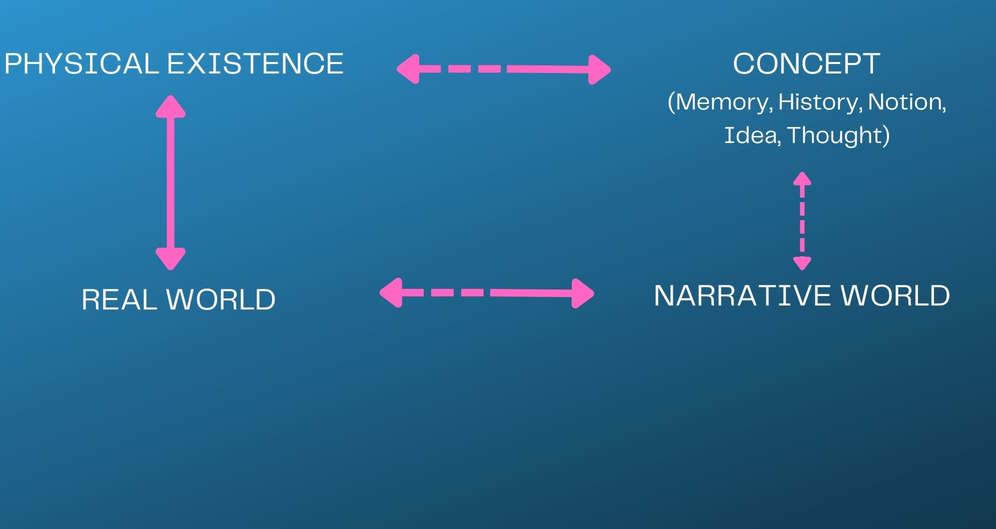

Returning to the issue of narrative worlds and whether they’re real, I proposed we could approach the matter as a connection to emotional (generally: affective) impact. If we tried to incorporate this into the same framework as above, regarding concepts and physical existence, perhaps we could come up with something like the diagram below.

Physical existence and the real world are very similar terms, but not identical. “Real world” contains “physical existence”, but there are things that are real which aren’t part of the physical world. Art, love, and femininity, are all very real. They might be incorporeal – though with physical expressions as well as causes – but they are certainly real.

If our physical existence informs a concept (memory, history, etc.), could we affirm the opposite? In some sense, yes. Our knowledge of history, science, and (sadly?) our emotions can influence the way we experience – and therefore ultimately understand and construct – reality and even physical existence.

Obviously, the degree to which you subscribe to this notion depends on whether you’re an empiricist (there’s an out there reality which we can access with our senses) or an idealist (perception is reality). Personally, I’m finding it difficult to accept the claim that concepts can influence an “out there” reality, but I’m open to discussion – philosophical, rather than scientific!

Similarly, it’s obvious that narrative worlds and concepts inform each other (in a way: art imitates life imitates art), though the exchange is more ambiguous – hence the fully dotted line. It’s equally evident that, if concepts can somehow influence physical existence (even subjectively speaking, in the way we individually construct “our” reality), narrative worlds are real in the sense they can affect “the” real world.

If Narrative Worlds Are Real, What Isn’t Real?

An excellent question, to which I have no good answer. Still, I can also tell you this: If everything is real, nothing is. In other words, to treat everything as real renders the idea meaningless.

One way out would be to treat reality as a gray area. All things are real, but some things are more real than others. In such a framework, we would call e.g. a rock falling on our head as “fully real”, the pain we feel as “pretty damn real”, the memory of a previous such occasion as “real”, and the vicarious understanding that others would hurt too if it happened to them as “fairly real”. We might also recall reading a novel about such an event and also call it “fairly real” – particularly if we might suspect the author expressed personal recollections.

It might feel tempting to simply say “Ah, screw it”, and call everything we experience as real and everything we see in a novel as imaginary. But that would feel like a simplistic answer to a complex problem.

How About Simulations?

Sims 4 is one of my favorite games. I’ve been playing it for years, using the same characters. Here’s an image of them.

As a first thing, we could talk about narrative worlds and reality in the context we’ve done so far: Experiencing the game affects my thoughts, emotions, ideas, and indirectly the real world. But going beyond that, sooner or later we’ll face a more complex question: Are the characters themselves real, or merely realistic?

Again, one could confidently say “Don’t be an idiot, of course they’re not real”, and again I would pose a “not so fast” objection. You see, to ask whether a character in a simulation is real or not is not the right question.

Rather, we should be asking whether such a character is conscious and self-aware.

“I think therefore I am” is the only claim to reality we really have; that’s it. We might be a simulation ourselves – or a brain in a vat, in the Matrix, tricked by a devil, take your pick – but we are real in the sense we have consciousness which the Sims characters do not – or so I assume at least!

Take our consciousness away, and there is little to separate us from Sims characters, even if we really are made of organic matter, rather than bits of information (which isn’t a given).

Sleep well tonight; nobody will turn off the computer!

Right?

I don't show you ads, newsletter pop-ups, or buttons for disgusting social media; everything is offered for free. Wanna help support a human internet?

(If you'd like to see what exactly you're supporting, read my creative manifesto).