May 22, 2023

Are Narrative Worlds Real? Reflections on Metaphysics

As a child, whenever I got emotionally affected watching a film or reading a story, my folks would try to console me saying “It’s not real, don’t worry”. That didn’t help at all. To me, narrative worlds were real, more real than reality itself. After all, fiction and reality are not antonyms.

When we talk about the reality of imaginary worlds – narrative worlds, in our case – the discussion seems moot. “Of course narrative worlds are not real”, any random observer would likely utter with – not misplaced – confidence.

After all, when you follow the characters of a video game, you can always save your progress and restore if something goes wrong. Similarly, when you read about a lonely female programmer plagued by indecision, her life never leaves the confines of the novel. You can’t meet that woman, her actions don’t dictate yours and can’t change the world.

Or… can they?

The Reality of A Christmas Carol

In Charles Dickens’s novella, Scrooge’s mind acts as a literal creator of worlds – with meta- hints concerning the process of reading:

For the priorly unemotional old man, the space-time travels offered by the ghosts do become more real than “reality”, in that they allow him to explore a previously dormant side of his self, that is his emotional response. In Scrooge’s current situation, this aspect of reality does indeed contain a vital function.…Memory is present, not only as the building block of this synthetic, omnijective reality, but also in its ability to reinterpret and reform future and past alike. Effectively, by employing the time-travel motif, A Christmas Carol emphasizes the mutability of memory and hence “reality”.

Angelis, Christos. “Time is Everything with Him”: The Concept of the Eternal Now in Nineteenth-Century Gothic. Doctoral Dissertation. Tampere, Finland: Tampere University Press, 2017. Available from the repository of the Tampere University Press. pp. 153

In plain terms, A Christmas Carol portrays an example of an imaginary world that influences reality as a result of reinterpretating this reality. It does so within its own plot without a recourse to fiction. In other words, Scrooge doesn’t ostensibly change his ways because he reads a book, but because he faces a “higher-order” reality – not unlike some highly realistic virtual reality or, say, LSD-induced trip.

Nonetheless, the allusion is there: Narrative worlds are real, if they can change our understanding of reality.

Or not?

Narrative Worlds Are Real Insofar as Emotions Are

Let’s ask ourselves another question first: Are emotions real?

To me, this seems like a crucial element in the attempt to gauge whether narrative worlds are real. If emotions are real, narrative worlds are also real. This would be in accordance with the notion that a narrative world event – a child becoming emotional because of a film or a fictional character like Scrooge because of some… Victorian version of virtual reality – can influence the real world.

As I see it, the answer to this question is, yes, emotions are real. However, self-evidently, emotions are also incorporeal. This adds a footnote to the “reality” of emotions and narrative worlds alike.

The truth is, we are surrounded by concepts and feelings, states and ideas, that are all real in some way we define reality, and yet not in some other way.

The Metaphysics of the Past and the Connection to the Physical World

Is the past real?

After all, if the past is reconstructed by memory, it is (very) likely to be inaccurate – to some extent at least. The more common the memory and the more the physical evidence, the higher the accuracy.

Nobody in their right mind would claim ancient Egyptians didn’t actually exist and didn’t build the pyramids, but it is not beyond the realm of possibility that a scary event of my childhood was nothing more than a dream. I’m fairly certain it wasn’t, but – believe it or not – I’m less confident about that reality than that of ancient Egypt.

An important element of the way we understand reality is precisely this exchange between concepts and physical existence. In the example above, we have immense confidence in the reality of the past that we call “ancient Egypt” because of the vast number of physical evidence across many categories and verified by many different disciplines.

Physical reality isn’t unproblematic – just recall the ship of Theseus. But it has a unique claim to “real” reality that is less complicated than emotions, ideas, and thoughts.

The Exchange Between Matter, Concepts, and Worlds

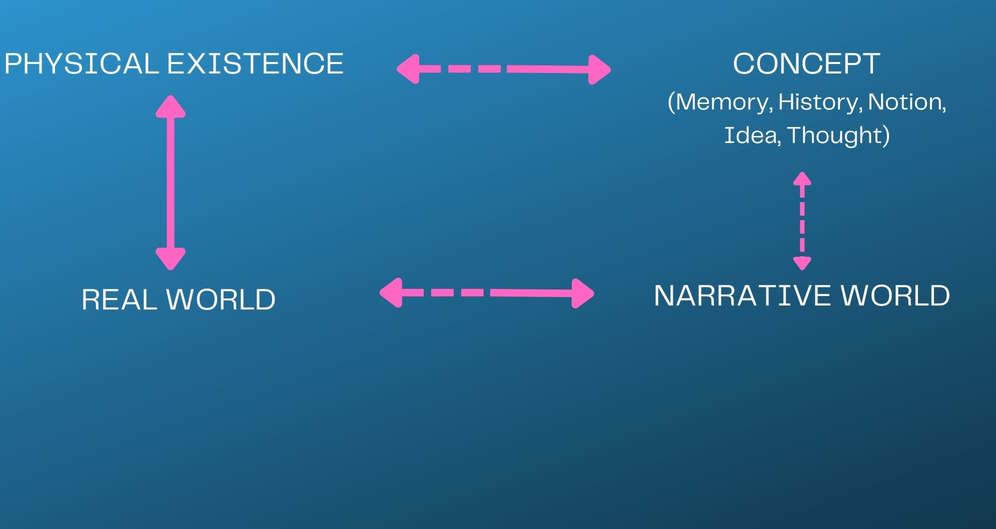

Returning to the issue of narrative worlds and whether they’re real, I proposed we could approach the matter as a connection to emotional (generally: affective) impact. If we tried to incorporate this into the same framework as above, regarding concepts and physical existence, perhaps we could come up with something like the diagram below.

Physical existence and the real world are very similar terms, but not identical. “Real world” contains “physical existence”, but there are things that are real which aren’t part of the physical world. Art, love, and femininity, are all very real. They might be incorporeal – though with physical expressions as well as causes – but they are certainly real.

If our physical existence informs a concept (memory, history, etc.), could we affirm the opposite? In some sense, yes. Our knowledge of history, science, and (sadly?) our emotions can influence the way we experience – and therefore ultimately understand and construct – reality and even physical existence.

Obviously, the degree to which you subscribe to this notion depends on whether you’re an empiricist (there’s an out there reality which we can access with our senses) or an idealist (perception is reality). Personally, I’m finding it difficult to accept the claim that concepts can influence an “out there” reality, but I’m open to discussion – philosophical, rather than scientific!

Similarly, it’s obvious that narrative worlds and concepts inform each other (in a way: art imitates life imitates art), though the exchange is more ambiguous – hence the fully dotted line. It’s equally evident that, if concepts can somehow influence physical existence (even subjectively speaking, in the way we individually construct “our” reality), narrative worlds are real in the sense they can affect “the” real world.

If Narrative Worlds Are Real, What Isn’t Real?

An excellent question, to which I have no good answer. Still, I can also tell you this: If everything is real, nothing is. In other words, to treat everything as real renders the idea meaningless.

One way out would be to treat reality as a gray area. All things are real, but some things are more real than others. In such a framework, we would call e.g. a rock falling on our head as “fully real”, the pain we feel as “pretty damn real”, the memory of a previous such occasion as “real”, and the vicarious understanding that others would hurt too if it happened to them as “fairly real”. We might also recall reading a novel about such an event and also call it “fairly real” – particularly if we might suspect the author expressed personal recollections.

It might feel tempting to simply say “Ah, screw it”, and call everything we experience as real and everything we see in a novel as imaginary. But that would feel like a simplistic answer to a complex problem.

How About Simulations?

Sims 4 is one of my favorite games. I’ve been playing it for years, using the same characters. Here’s an image of them.

As a first thing, we could talk about narrative worlds and reality in the context we’ve done so far: Experiencing the game affects my thoughts, emotions, ideas, and indirectly the real world. But going beyond that, sooner or later we’ll face a more complex question: Are the characters themselves real, or merely realistic?

Again, one could confidently say “Don’t be an idiot, of course they’re not real”, and again I would pose a “not so fast” objection. You see, to ask whether a character in a simulation is real or not is not the right question.

Rather, we should be asking whether such a character is conscious and self-aware.

“I think therefore I am” is the only claim to reality we really have; that’s it. We might be a simulation ourselves – or a brain in a vat, in the Matrix, tricked by a devil, take your pick – but we are real in the sense we have consciousness which the Sims characters do not – or so I assume at least!

Take our consciousness away, and there is little to separate us from Sims characters, even if we really are made of organic matter, rather than bits of information (which isn’t a given).

Sleep well tonight; nobody will turn off the computer!

Right?

This post is magnificent, yet so much remains unsaid! Although I like Wittgenstein’s proposal (of that which cannot be spoken, one must be silent), I like even more to speak of these (almost) impossible problems that remain under the name of metaphysics, despite all the efforts of the 20th century to eliminate it from thought (Wittgenstein himself, logical positivism, Heidegger, among many others).

What seems to me to be a key part of the problem is the lack of granularity (or resolution, as they call it in YouTube videos) of the language used to analyse and discuss the issues. Nouns like “reality” and adjectives like “real” have, not, an excess of meaning, but an immense lack of it. They are too light words, too applicable in too many contexts, too little or too poorly delimitable, almost impossible to restrict use to a studiable number of cases.

The pragmatic solution does not seem sufficient to me: real is everything that affects reality. Even though it may be a measure, this creates a huge chain of mediations when reaching people’s mystical, magical, religious and/or spiritual beliefs.

There seems to be something normative, in the sense of a correction from a kind of argumentative force, a convincing force, about the falsity of some beliefs. If someone were to claim, for example, that there is no violence against women or racist violence in the world today, that person would be factually wrong. But then why would that person assert that belief? Even if one strongly holds a belief, there is a way to argue that this person is wrong with lengthy argumentative demonstrations, linking facts to interpretations and data (sociological, psychological, economic, historical, etc.). Therefore, it is not enough to maintain a pragmatic relationship with reality, this kind of relationship (“only what affects reality is real”) needs some weight, I mean, some things affect reality in more intense or far-reaching ways than other things (think, for example, of how much you are able to change your city’s salary versus how much a mayor or councillor is able to change the salary of the same city).

Of course, empirical reality seems to take some precedence over other realities, taking a more important position in examples and argumentation. But since it is not the only component of reality (we experience non-empirical things, such as abstractions, rules, assumptions, etc.), it is not enough to arrive at arguments or analogies with empirical experiences. We cannot even settle on the decision that we only have empirical experiences, it seems possible to have experiences not regulated by sensations. Or to have sensations of nonsensible things.

And as much as I say all that and have more to say. Nothing will suffice for the topic.

Indeed, this is one of those topics that we could be discussing for hours, only to have scratched the surface. Like infinite regress, reality is largely beyond our reach (a rather peculiar state of affairs, if you think about it).

I think one reason is that we’re inside the very system we try to analyze. This i) “pollutes” the observation, since we cannot effectively separate ourselves from the object of the observation; ii) in a sense renders it impossible to compare it against another system.

This is similar to what David Chalmers argues in his text on the metaphysics of Matrix, linked at the end of the post:

I even think it’s worse than that, by worse I mean more complex. A human psyche is a worldly entity, something that exists in the world and is formed by contact with and appropriation of that world. But that same psyche can conceive at least the idea of another world, even if it cannot detail the concrete elements of that other world. This mere fact indicates that, in some way, this psyche cannot be entirely subsumed as an element of this world. Or, even worse, that the term “world” names something capable of holding several worlds within itself. All this greatly complicates the discussion, whichever way out is taken. If a psyche possesses an extramundane element, then elements alien to the world inhabit the world and compose themselves with elements of that world. If the one world is a plethora of worlds, then it remains to be explained how its composition can be perceived and appropriated as a unity.

Out of all this, I am left with the fascination of understanding how understanding, a worldly activity, can attempt to comprehend the world. It’s like a brain, a piece of nature, trying to understand nature. All that seems, to say the least, fascinating.

All of this clearly and evidently passes through language. Language reveals the world as the world, but distances it as it provides it. It is something mundane, to be sure, but it exists as extramundane. Language is simply the strangest thing that exists, if it is a thing and if it exists at all. For even if it is said to exist (for it would seem a nonsense to deny its existence), it is impossible to say that it exists just as a chair exists, but also just as a feeling exists. Also, because to exist is, above all, a word.

The whole idea of reality is a paradox in a way because we never experience reality directly. Even something as ‘factual’ as stubbing your toe is not felt by the toe. That interaction with the world outside our skin is turned into an electrical impulse that travels to the brain, is mediated by chemicals in a zillion synapses, and then it’s the /brain/ that tells the toe ‘you’ve been hit!’ So right from the very start, errors are not only possible but likely.

This also explains why no two people ever experience a moment of reality in the same way. There are simply too many points of mediation between the ‘event’ and the individual’s reaction to it.

And that’s not counting the deliberate conditioning supplied by ‘the group’. A child has to learn what the world outside its skin is all about. It’s /taught/, and that first conditioning is incredibly powerful. Teach a boy that it’s ‘bad’ to play with dolls, or cry, or like girlie things, and that belief will be next to impossible to shift in later life.

So…in a very roundabout way, why shouldn’t narrative worlds feel real. If the sensations reaching the brain are close enough to the ‘real’ thing then the brain has no reason to downgrade them. I suspect this is why dreams feel so real while we’re experiencing them.

The danger I see is that there will come a time when artificial sensations will simulate what we expect from reality so well that the brain won’t be able to tell the difference.

It’s also fascinating that, in a sense, our brain is a limiting organ; a filter, so that sensations don’t happen all at once. And we literally are the center of the universe, because that’s the only way we can experience it.