Note: the following article analyzing Count Dracula’s attack on Mina Harker (in Bram Stoker’s Dracula) is a modified excerpt (pp. 123-124) from my doctoral dissertation, “Time is Everything with Him”: The Concept of the Eternal Now in Nineteenth-Century Gothic, which can be downloaded (for free) from the Tampere University Press pages. For a list of my other academic publications, see the related page of my website.

Dracula’s Attack on Mina: The Issue of Ambiguity

The borders of the attack scene are somewhat blurry. Not only because the attack is implied to have taken place over a period of several nights, as Dracula tells Mina “it is not the first time, or the second, that your veins have appeased my thirst!” (Stoker 2003, 306), but also because the events that lead to this attack are similarly hazy.

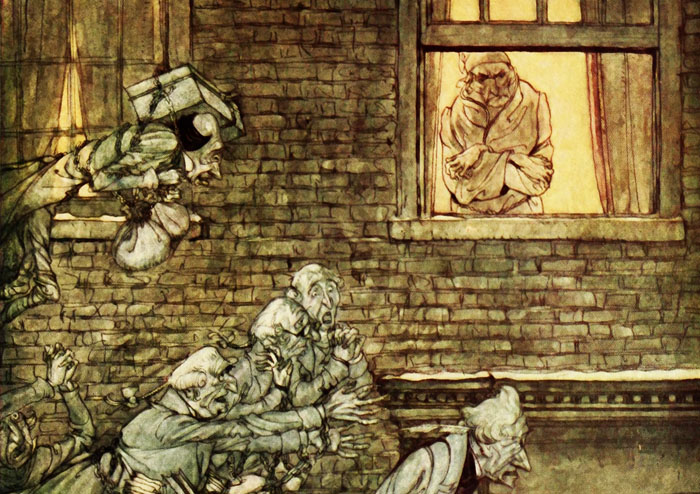

Examining the facts from the night between September 30th and October 1st, Mina mentions how she cannot remember how she fell asleep but that she does recall an eerie stillness covering everything (Ibid, 274). What she construes as dreams or her imagination is in actual fact Count Dracula in the form of mist, invading the room like a “pillar of cloud” with red eyes (Ibid, 275).

Initially Mina is fascinated by the pair of red eyes that shine in the dark, but horror overcomes her when she recalls the three female vampires Jonathan encountered back in Transylvania and Dracula’s castle.

(more…)