At the banquet following my doctoral defense, a colleague asked me about my future plans. I mentioned that, among other things, I planned to continue writing fiction. That colleague then said something that made quite an impression on me: “The problem with writing fiction nowadays is that there are more writers than readers”. Those words really resonated with me. I don’t know if this is actually the case – instinctively I would say “it can’t be” – but I’m afraid if not literally true, then it’s pretty damn close. You don’t need me to tell you what that means in terms of supply-and-demand economics.

In the first article written for this blog, I had said this:

I hope I don’t come off as too self-important when I say that people like me […]with the artistry to create and populate fictional worlds and characters (that are still allegorically linked to “reality”), would have been revered masters and teachers in another time and another place.

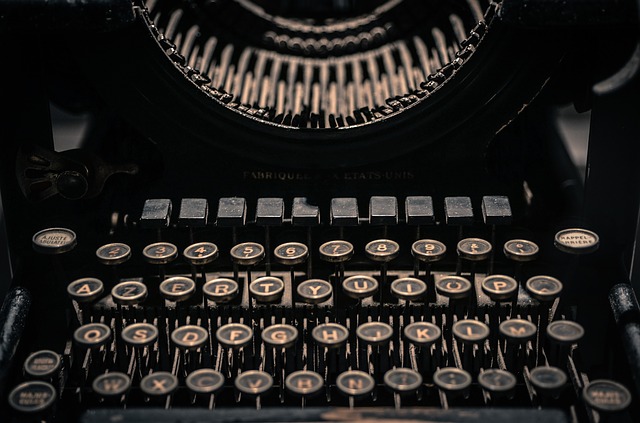

This is an extreme example of the very same situation, only in reverse. It alludes to times when writing (that is, literacy itself) was not a given. To be able to write and write fiction, to boot, was something akin to witchcraft. I suppose we tend to be mesmerized by things we don’t understand; to me, knitting is like quantum physics.

But nowadays, although there might not necessarily be more writers than readers in a literal sense, the number of people who have the possibility to write something they call fiction, publish it in some way, and make it accessible to a wide – indeed an international – audience has skyrocketed.